Dartmouth College Library

Hanover, NH 03755, USA

Copyright: Trustees of Dartmouth College, 2002.

by

Hanover: Dartmouth College Library, 2002

All photographs courtesy of the Dartmouth College Library.

© The Trustees of Dartmouth College, 2002

| Illustrations | vi |

| Acknowledgements | vii |

| Chapter One: Origins, 1769–1819 | 1 |

| Chapter Two: Rebuilding, 1819–1874 | 9 |

| Chapter Three: Growth and Transition, 1874–1910 | 22 |

| Chapter Four: From Wilson to Baker, 1910–1928 | 33 |

| Chapter Five: Challenge and Change, 1929–1950 | 47 |

| Chapter Six: The Morin and Lathem Years, 1950–1978 | 62 |

| Chapter Seven: Into the Future, 1979–2002 | 77 |

| The Woodward Succession | 92 |

| Library Locations, 2002 | 93 |

| Sources and Suggestions for Further Reading | 94 |

| Index | 97 |

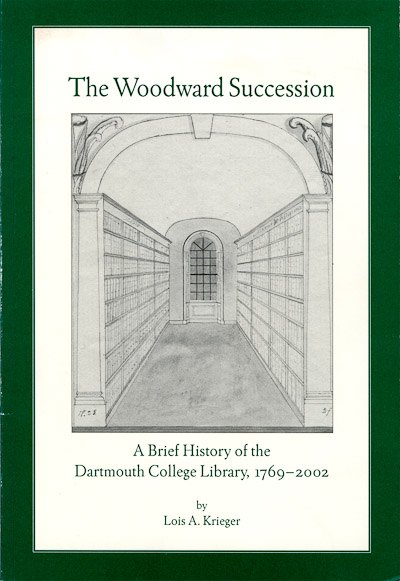

| The Woodward Room in Baker Library | viii |

| Dartmouth Row in 1851 | 10 |

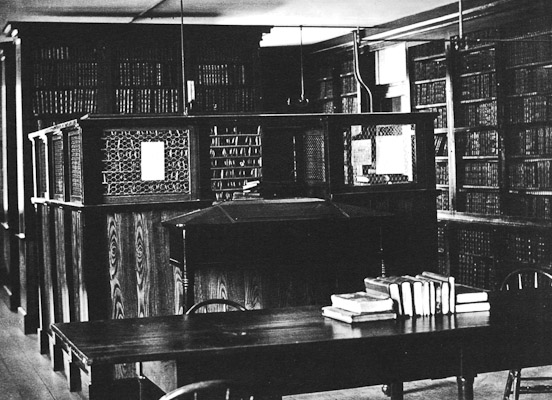

| United Fraternity Room in Reed Hall | 13 |

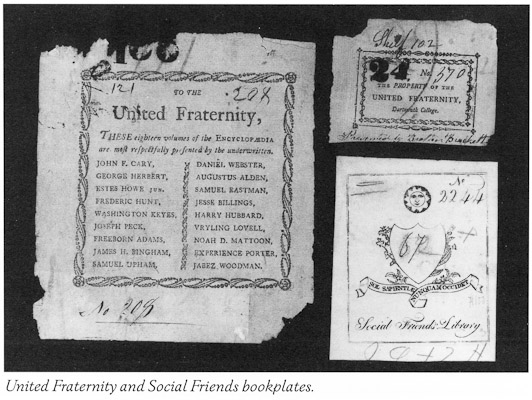

| United Fraternity and Social Friends bookplates | 20 |

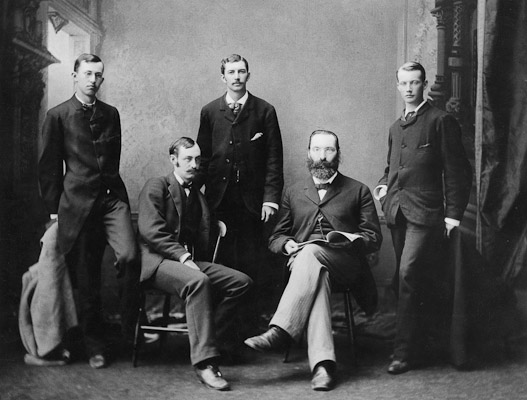

| The Library staff in 1883 | 25 |

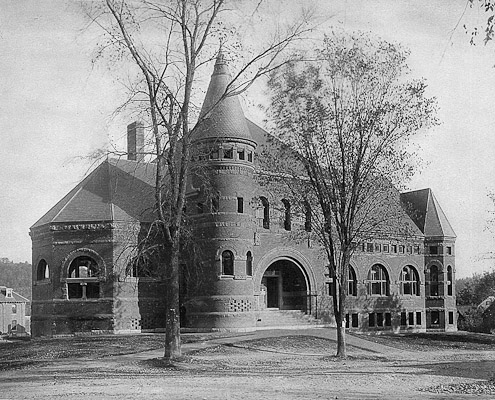

| Wilson Hall in 1885 | 27 |

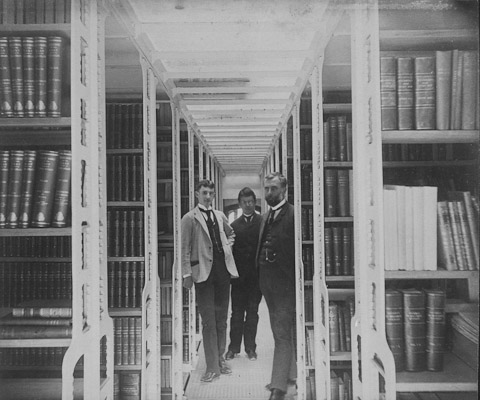

| Third–floor stacks in Wilson Hall, 1885 | 29 |

| Baker Library under construction, 1927 | 37 |

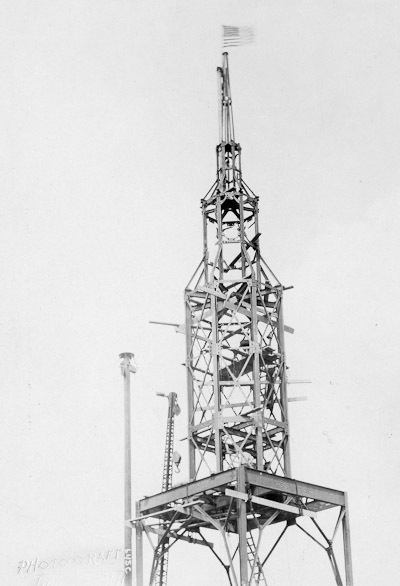

| Baker Library tower, 1927 | 39 |

| The completed Baker Library | 42 |

| The Library staff in 1928 | 44 |

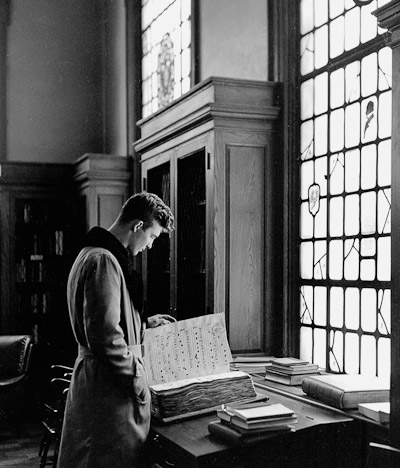

| In the Treasure Room of Baker Library | 46 |

| In the stacks | 57 |

| Robert Frost talking with students in the Treasure Room | 60 |

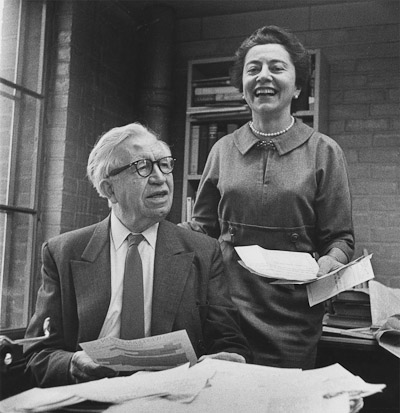

| Vilhjalmur and Evelyn Stefansson | 64 |

| The Medical Library in Baker Library | 67 |

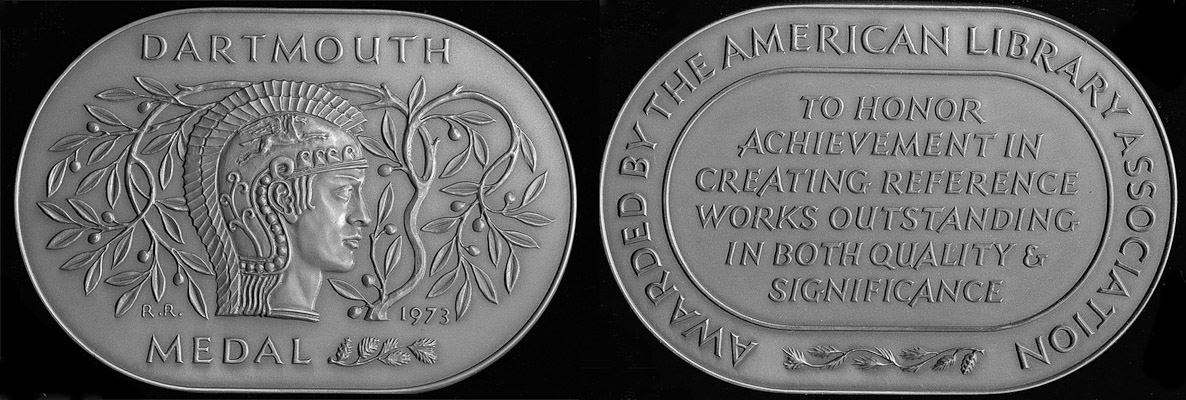

| The Dartmouth Medal | 72 |

| Mickey Mouse hands | 76 |

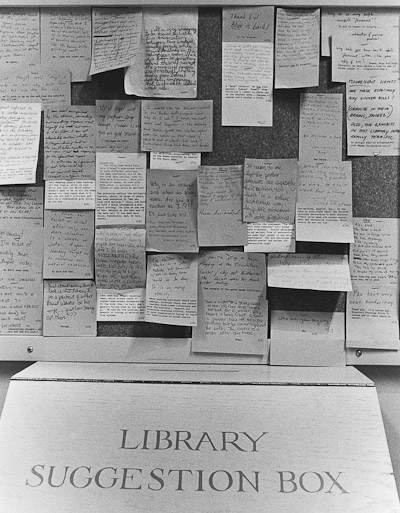

| The Suggestion Box | 81 |

| The entrance to the new Berry Library | 84 |

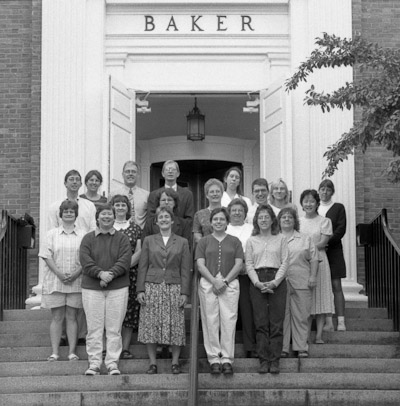

| The Library Staff in 2000 | 86, 87 |

| Under the watchful eye of Daniel Webster | 90 |

If I properly thanked everyone who provided aid and comfort while I was working on the history, this acknowledgements ‘page’ would be longer than the book itself. Special thanks are due some special people:

Philip Cronenwett, Special Collections Librarian, and my sister Barbara Krieger, Archival Specialist, for advice, encouragement, and exceptional knowledge of College and Library history; everyone on the Rauner Special Collections staff, who chided me for the indecipherable handwriting on my call slips but nevertheless fetched, carried, photocopied, and stored voluminous amounts of books and archival material; Derika Avery, for cheerfully putting up with my erratic schedule, obtaining boxes of documents from Records Management, and finding a comfortable place for me to work with them; Virginia Close, Kenneth Cramer, and John Crane, for reading a really rough draft and providing invaluable comments and corrections; Patsy Carter, Virginia, Ken, and the other members of the old–timers' breakfast group, for sharing stories and reminiscences; and the staff of the Storage Library, for efficient service and patient tracking down of elusive references.

I also wish to thank Richard E. Lucier, 17th Librarian of the College, who initiated and funded the project, and his predecessors, Edward Connery Lathem and Margaret A. Otto, with whom I worked for more than thirty years. To the staff of the Dartmouth College Library, past, present, and future, this book is respectfully dedicated.

The Woodward Room in Baker Library with the remaining books from the first Library of the College.

Dartmouth was the last of the nine colleges founded in colonial America before the Revolution. The early history of its Library is an integral part of the folklore of the College's origins. The growth and development of both College and Library paralleled in some ways those of the older institutions; in other ways, the College and its Library took quite different paths.

Eleazar Wheelock, the founder of Dartmouth College, had acquired a collection of books, primarily testaments, sermons, and religious tracts, for two schools he had founded in Connecticut before moving to New Hampshire. This collection is usually considered the nucleus of the College's Library, and its existence is the reason for the often–repeated statement that the Library predated the founding of the College.[1]

Wheelock was born in 1711 [O.S.], the son of a farmer and church deacon in Connecticut. He was graduated from Yale in 1733,[2] and in the following year became a minister in a parish in a section of Lebanon, Connecticut, called Lebanon Crank (now known as Columbia).[3] Wheelock occasionally supplemented his income by tutoring boys at his Latin School to prepare them for college. Wheelock was also interested, as were many other eighteenth–century New England clergymen, in converting the Indians to Christianity. One of his students was Samson Occom, a member of the Mohegan tribe. Occom had heard of Wheelock and other preachers in the religious revival known as the Great Awakening and wished to study at the Latin School. He later became a preacher and missionary. Wheelock's success in preparing Occom for the ministry encouraged him to accept other Indian boys (and, later, girls) as students. In 1755 Colonel Joshua More (in later documents, spelled Moor) gave about two acres of land and

Between 1762 and 1763 Wheelock made several appeals for the support of his school to George Whitefield, a Great Awakening preacher who had been a strong influence on his ministry, and others in England and Scotland who supported the idea of Christianizing the native population. Records from 1764 onward note gifts from Rev. Dr. A. Gifford, of London, and the Society for the Diffusion of Christian Knowledge among the Poor.[5] In 1765 Wheelock sent Occom and the Reverend Nathaniel Whitaker[6] on a mission to Great Britain for the purpose of raising funds and collecting books for the school. In 1769, Wheelock obtained a charter from King George III, with the second Earl of Dartmouth as a Trustee, for a more ambitious version of the school, to be called Dartmouth College. He also obtained a grant of land in New Hampshire from the province's royal governor, John Wentworth. Wheelock considered many towns before deciding on Hanover as the location for the new school. In the fall of 1770, he moved his school, including the collection of books, to Hanover.

The story of the College's first years in the wilderness has often been told. In the first year, a somewhat primitive building sufficed for all of the institution's needs. At the first meeting of the Trustees, on October 22, 1770, Bezaleel Woodward, a graduate of Yale, was appointed a tutor of mathematics and natural philosophy, and in the following year the Trustees granted him “about an Acre” of land for a dwelling.[7] In their meeting of 25 August 1773, the Trustees

Voted. That Bezaleel Woodward Esqr be, and hereby is appointed Librarian for this College.

Voted. That the Library be kept in the Southwest Chamber of Mr. Woodward's house till ordered otherwise.[8]

Income from a bequest of £100 from Theodore Atkinson Sr. and the Reverend Diodate Johnson's bequest of £150 and his library were of great importance in the establishment of the collection.[9] Dr. Jeremy Belknap, an early historian of New Hampshire, visited Hanover for Dartmouth's 1774 Commencement. In his diary, he noted

Among these “very good books” in the fledgling Library were many duplicate copies. The earliest known catalog is a four–page manuscript list dated January 1775.[11] In the previous year, Woodward had begun recording Library transactions in a notebook that cannot now be found. Length of loan and the fee for borrowing varied with the size of the volume; it cost more (sixpence) to borrow a folio than a quarto (fourpence), but the borrower could keep it longer—four weeks instead of three. In his notebook, Woodward listed the members of the College, including students, in order of seniority, so apparently anyone in the College could withdraw books.[12]

Wheelock, with careful management and continued assistance from supporters, had been able to keep the young institution open during the years of the American Revolution, even though John Wentworth, the colonial governor, had fled to Nova Scotia, causing some disruption in the flow of donations. Hanover's comparative isolation helped to minimize disruption of College activities. Woodward, in addition to his responsibilities as Tutor and Librarian, was also active in town affairs, and may also have needed the Library rooms in his house for family use.[13] The records for the 20 May 1777 meeting of the Trustees note that the Library was to be moved “to such part of the College as the President shall judge proper,” and that the president, “with the advice of the Tutors,” was to appoint a Librarian. Wheelock may have overseen the Library himself, possibly with Woodward's assistance; but a new Librarian was not appointed right away. The Library was moved to a room on the second floor of Old College, the “principal College building . . . near the southeast corner of the Green.”[14] On 30 August 1779, the Trustees voted to appoint John Smith the second Librarian.[15] In the same year, Eleazar Wheelock died; his son John, having been named in Eleazar's will as his successor, became Dartmouth's second president.

Smith had been graduated from the College in the Class of 1773. He was a tutor in the College from 1774 to 1778 and professor of Latin, Greek, and Oriental languages from 1778 until his death in 1809. He was also a minister of the College Church and kept a bookstore in Hanover. His tenure as Librarian is one of Dartmouth's longest,

At this time the College Library remained small. Soon after the end of the Revolution, students were beginning to collect libraries of their own. In the older colleges, literary and debating societies had been founded in the years leading up to the Revolution, as undergraduate life reflected the public's interest in the great issues capturing the attention of the society at large. At Dartmouth, the first literary and debating society was founded in 1783, the year that the Treaty of Paris, ending the War for Independence, was signed. Called the Society of Social Friends and known familiarly as the “Socials,” it began to acquire a library. In 1786, some members left the Socials to form a rival group, the United Fraternity, known as the “Fraters,” that also built up a library. The two societies maintained a strong rivalry for many years, most importantly in literary debates and in “exhibitions"—the dramatic oratory displayed at specific times during the College year, especially at Commencement. The societies treasured their libraries both for leisure reading and as sources for preparing the debates and exhibitions. The libraries were supported by taxes levied on their members and by donations of books by the graduating class. The seniors in each society competed to contribute the best books as fiercely as they vied in Commencement oratory.

That the society libraries played an important part in the students' lives is evident; what is less clear is whether they, or the College Library, had much to do with the students' classroom work. According to a standard history of the College, there is no mention of the early curriculum until 1796, when it included “learned languages,” mathematics, English and Latin composition, and “the elements of natural and physical law.”[16] All students followed the same prescribed course of study. Classrooms were called “recitation” rooms; students replied orally to the tutors' questions to show that they had mastered the subject matter. From the vantage point of the twenty–first century, it is perhaps too easy to make light of the inadequacies of the colonial colleges' library holdings. Yes, they were small, and were strong in theology and classics and little else; but the colleges were in most cases founded primarily to produce ministers, and the collections reflected the requirements of the curriculum. Books were valued and often not easy to acquire, so it should not be surprising that there were severe restrictions on access and withdrawal.[17] However, it should also not be surprising that the students wanted to acquire libraries of their own; and often, the rules for use were very much the same as those for the institutions' libraries. In 1796 the Trustees issued the first set of rules for the College. It covered admission, curriculum, student behavior,

In 1783 the College Library was moved to President John Wheelock's house, pending construction of Dartmouth Hall, intended to replace Old College, which was in a poor state of repair. Construction was begun in 1790 but not completed until 1791, at which time the books were returned from Wheelock's house and installed on the second floor of the new building. A fire in Dartmouth Hall in 1798 necessitated the removal the books once again to the President's house, but they were returned quickly and later moved to a larger room when the building was remodeled between 1828 and 1829.[20] The societies' libraries were usually kept together from about 1790 until 1799, when the rivalry and dissension between the two led to the breakup of what had been referred to as the ‘federated' library. The books were kept for a number of years in members' rooms, but the separation had renewed the rivalry concerning the building up of the collections, and very soon each society had built a collection equal in size to that of their combined libraries. As the collections had clearly outgrown students' study rooms, the College in 1805 provided a room for each society's library in Dartmouth Hall.

Hours of opening for the College Library gradually increased. By this time, the Librarian was beginning to consider his duties “arduous"—the collection had reached about 3000 by 1799—and in 1808 the Trustees tried to make his life easier by requiring students to “receive and return books at the library as nearly in alphabetical order as will be convenient for the librarian.”[21] Since we do not have circulation records for that period, we cannot tell whether it was the students or the books that were supposed to show up at the Library in such order.

The years 1809 and 1810 saw two turning points in the Library's early history. In 1809 the Trustees authorized the publication of a catalog of the Library's holdings, which was issued sometime between 1809 and 1810. This first printed catalog brought up to date Woodward's 1775 manuscript. Professor Smith died in the spring of 1809;

Both Smith and Shurtleff were clergymen. Shurtleff, Class of 1799, was the Professor of Theology, and in 1804 a majority of members of the College church had preferred him as pastor to Professor Smith, who was supported by President John Wheelock. The issue was partly one of religious doctrine, but Wheelock's domineering stance with the Trustees foreshadowed the larger conflict to come.

The 1769 charter that established Dartmouth College named Eleazar Wheelock President and stipulated that he could choose his successor, but added that the Board of Trustees (limited to twelve members by the charter) could discharge the appointee. From around 1811 and several years thereafter, John Wheelock's quarrels with the College Trustees, beginning with the church controversy and continuing with other issues of College governance, became more numerous and bitter.[23] Several members of the board died, and the Trustees elected replacements opposed to Wheelock, who was, by most accounts, “imperious and demanding." Wheelock published an attack on the Trustees and also addressed a pamphlet to the General Court, New Hampshire's legislature, stating that the Trustees had violated the charter by various offenses. The legislature, in turn, passed a bill calling for a committee to “investigate . . . the acts and proceedings of the Trustees.” The Trustees, in their meeting of August 1815, by a vote of 8 to 2 removed Wheelock from the presidency, appointed the Reverend Francis Brown in his place, and issued a refutation of the charges in Wheelock's tract. College, town, and the entire state took sides, making their arguments in local newspapers; party politics played a role. In June 1816, the state legislature passed “An act to amend, enlarge and improve the corporation of Dartmouth College.” The law changed the name of the institution to Dartmouth University and added nine trustees to the board, making a total of twenty–one; John Wheelock was the University president. The College Trustees refused to comply with the law, and the battle was joined.

For several years, the two separate institutions existed on Hanover Plain, in a strange mixture of amiability and conflict. The University had a separate, very small, faculty and its own president, William Allen, who had succeeded his father–in–law, John Wheelock, upon Wheelock's death in 1817. Both College and University held classes in adjacent or possibly even in the same buildings. A committee of three of Hanover's leading citizens were appointed by the University trustees to take possession of the College's Chapel and Library. College President Brown at first refused to

In February 1817 the College Trustees initiated a lawsuit, referred to the Superior Court of the State of New Hampshire, against William Woodward, with the object of recovering the Trustees' minutes, the College charter and seal, and other items. Woodward had been in possession of these documents when he was Treasurer and Secretary of the College, and kept them when, as a supporter of Wheelock, he became a trustee and treasurer of the University. On 6 November 1817, the court decided in favor of the University.

Anticipating the decision and believing their libraries in jeopardy under University control, Society members had begun packing books and moving them to student rooms for safekeeping. Rufus Choate, Class of 1819, later a distinguished jurist, was librarian of the Social Friends, and had rented a separate room in the house where he was boarding to keep the Socials' books. On 11 November 1817, Professors James Dean and Nathaniel Carter, of the University, rounded up a “crowd of village roughs" and attempted to take possession of the Society library rooms; while the books may have been private property, the rooms were deemed the property of the University and thus subject to seizure. The Social Friends' library door was demolished—according to one newspaper report, by an ax. The United Fraternity, meeting in a nearby room, overheard the ruckus and came to the Socials' defense. The assembled students greatly outnumbered the professors and detained them in the rooms until the remaining books could be taken away to safety. Then the invaders, except for the professors, were marched out of the building through a gauntlet of menacing defenders, armed with “sticks of cord–wood.” The professors, each accompanied by four students, were escorted home, apparently with some degree of civility; the students were determined not to “be charged with insult or discourtesy.” At least one of the professors was grateful enough for the safe passage to tip his hat and thank his escort. Nine students were arrested “for trespass and false imprisonment” and brought before a Justice of the Peace; one of the nine brought a countercharge of riot against Dean and Carter.[24] Both groups appeared before a grand jury, which declined to issue any indictments, deciding that in comparison with the greater issues facing the institution, the library incident was “considered of little consequence.” The “riot” or “fracas” was nonetheless featured in many local newspaper accounts, and doubtless was viewed by the townspeople

The College Trustees appealed the New Hampshire court's decision to the United States Supreme Court, with a result firmly implanted in the minds of every incoming Dartmouth first–year student. Uncounted books and articles dealing with the constitutional, educational, and business implications of the case have been written; it would be foolhardy here to give more than a brief summary. The College was represented by extremely able counsel, including Daniel Webster, Class of 1801, whose argument before Chief Justice John Marshall is a fundamental part of Dartmouth lore. Verbatim texts of arguments before the Supreme Court were not at that time published; the account of Webster's speech comes from the correspondence, many years later, between Chauncey A. Goodrich and Rufus Choate. As Goodrich recalled, Webster asserted that the state legislature had taken “that which is not their own” and subverted the intent of the donors. Webster implored the court not “to destroy this little institution,” with the famous peroration, “It is, sir, as I have said, a small college, and yet there are those who love it.” It is not difficult to see in this statement an unconscious echo of Dr. Belknap's small library, with the very good books.

On 2 February 1819, Chief Justice Marshall read the Supreme Court's opinion overturning the state court's decision, declaring that the College charter was a contract under the protection of the United States Constitution and that the legislature's actions were “repugnant” to that constitution. The University administration gave in a bit grudgingly, but eventually William Allen returned to President Brown the keys to the College buildings, and Dartmouth University ceased to exist.

In naming the rival institution “Dartmouth University,” the New Hampshire legislature may have intended nothing more than to give a grandiose name to their creation, although some legislators were thinking of a school of law to add to the already–existing medical school. Yet once the case was decided, the very word “university” took on something of a sinister meaning. For many years to come, the memory of the Dartmouth College Case fixed in the minds of presidents, students, and alumni that Dartmouth should remain a college, not a university, an idea that greatly affected the development not only of Dartmouth College as an educational institution, but also of its Library.

After so many years of chaos, the College Library, no different from the College as a whole, was in need of serious attention. That portion of student fees meant for the Library had had to be used for more pressing needs, and many volumes had been lost or defaced. During the precarious years of the College/University conflict, the Trustees had briefly considered selling part of the Library collection for around $2100, to raise money to defray some of the cost of the legal proceedings, but there were no takers.[26] Following the Supreme Court's decision, the publisher Isaiah Thomas, of Worcester, Massachusetts, made a substantial donation of 470 volumes. Thomas had connections with the College through the American Antiquarian Society, of which he was the founder. Samuel M. Burnside, Class of 1805, was the Society's recording secretary, and former President John Wheelock had been a member. Dartmouth had awarded Thomas an honorary AM degree in 1814. In a letter to Ebenezer Adams (Class of 1791 and later a professor), Thomas wrote of his “sentiment of high esteem and respect for the Rev. President, and other officers of this Institution.” [27] Thomas was well known and respected, and his donation was a sign of Dartmouth's renewed vigor and reputation.

John Aiken, a tutor in the College who later became a lawyer and manufacturer, was named Librarian in 1820.[28] The Trustees also appropriated $400 for the Library. Aiken served only two years. Charles Bricket Haddock, of the Class of 1816, who had become Dartmouth's first Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory in 1819, was asked by the Trustees to examine, with the President, the condition of the Library, possibly to

In 1822, the Trustees voted that whoever was appointed Treasurer of the College was also to act as Secretary, Librarian, and Inspector of Buildings and Inspector of the Museum.[30] This appears to be an unusually heavy load, even in an era when life was simpler and bureaucratic responsibilities were lighter. The new Treasurer, Timothy Farrar, Class of 1807, must have felt that rather too much was being asked of him. He had recently published a detailed study of the issues in the Dartmouth College Case,[31] which had taken up a considerable amount of his time. At the same session, the Trustees appointed Oramel S. Hinckley as librarian pro tem. Hinckley's name never appeared in the lists of College officers for the approximately year and a half that he served; he is mentioned once more in the Trustees' records, requesting labels for books in the Library.[32] Later in 1823, Farrar felt able to take up his duties as Librarian, and served until 1826.

The Trustees issued an updated set of laws for the College in 1822 and 1828, setting a quarterly fee of $2 from the students for the Library. They also authorized publication of another catalog, but it was not completed until 1825.[33]

The literary societies, in existence since the late eighteenth century, were chartered in 1826 and 1827. Many such societies on other campuses were similarly incorporating, primarily for the protection of their libraries, which were “too valuable to be left to the care of voluntary associations without legal rights or responsibilities.”[34] The charters gave the societies the “right to hold property and transact business.”[35] The libraries of both the Social Friends and United Fraternity continued to grow, and hours of opening were increased. There were still limits on the number of books that could be drawn: Seniors were allowed four books at a time, juniors three, and freshmen and sophomores two. The Social Friends set aside a separate collection of books on classical studies in the “Philological Room." Students gathered in this room for study; a later College Librarian, Marvin Bisbee, considered this study an independent example, or forerunner, of departmental library collections and the seminar method later developed in Germany and, in America, by Johns Hopkins.[36] By 1824,

In 1826, Professor Haddock was appointed Librarian, at a salary of $50 a year. He was a nephew of Daniel Webster and a member of the class of 1816; he received a degree from Andover Theological Seminary and was ordained a Congregational minister before returning to Dartmouth. An effective and popular speaker and writer, he was an impressive figure on campus, handsome and dignified, bearing more than a passing resemblance to his uncle. More than was customary at the time, he was involved in undergraduate life, particularly in the literary societies. Although he did not desire a career in public life, he was actively interested in the issues of the day, particularly public education. He was a member of the state legislature from 1845 to 1848 and was New Hampshire's first Commissioner of Common Schools, advocating public high schools and better training and pay for teachers.

Haddock, like his predecessors, also held a teaching post at the College. It is difficult to discern what importance these early Librarians attached to their Library responsibilities. Haddock was the first to leave behind, in published articles, lecture notes, and letters, some indication of his thoughts on books and reading. He was, of course, a firm believer in the worth of the ancient classics and the Bible, but he also acknowledged the value of contrary opinions. In the notes for one of his popular lectures, “The Way to Read a Book,” he was aware of the problem of choosing a worthy book to read, even in a simpler time when choices were fewer:

It is much like choosing a wife; Adam had no difficulty at all in that; but his posterity sometimes finds it hard to fix upon one as best among so many that are good—

A book is not necessarily good because it is old, or bad because it is new; Shakespeare was “new” in the sixteenth century. He felt that “a single reading is seldom sufficient . . . a cursory reading is like the accidental meeting of a stranger.” A more thorough reading makes the author a lifelong companion, and cultivates a taste for the best in literature.[38]

As in other eras, some students' love of literature and appreciation of books contrasted with other students' careless treatment. In part, the latter view was an expression of the students' dissatisfaction with the College Library, especially compared with the society collections. According to one source, the Trustees' decision to move the College Library from the second to the first floor of Dartmouth Hall was at least in

United Fraternity Room in Reed Hall.

The college library was very small, and had been so collected that it contained few books that either the instructors or the students wished to read. The chief dependence of the latter for reading was upon the society libraries, in which they took so much pride, and to the increase of which they contributed with so great liberality in proportion to their means.[39]

By the late 1830s, enrollment had increased considerably, and appeals were made to alumni and others for funds to erect a new building. A legacy from a Trustee, William Reed, provided the means for new construction. Reed Hall was completed in time—just—for the 1840 Commencement. The entire second floor was given to the College and society libraries;[40] the Trustees must have regained confidence in students' restraint concerning tossing books from an upper floor. In 1841, Professor William Cogswell, of the Class of 1811, formed the Northern Academy of Sciences, using

Various sources note that the move was hasty. Repercussions from that haste may have been the underlying cause of a dispute that erupted between 1840 and 1842 over management of the Library. Although Roswell Shurtleff had not held the position of Librarian since 1820, he still retained an interest in its condition. As a faculty member, he asked the Trustees, at their meeting of January 1840, to appoint a committee to look into the Library situation. At the August 1840 meeting, Shurtleff and Trustees Samuel Fletcher, Class of 1810, and Zedekiah Barstow were requested to carry out the investigation.[43] The text of their report has not survived, but Haddock's refutation of the charges gives ample evidence of the main points of contention: a dirty Library room and lost books. In two letters to Trustee Charles Marsh, dated August 1842,[44] Haddock noted the haste with which the books were moved from Dartmouth Hall to Reed; some sweeping of the floor was done before paint in the room had hardened, so dirt had stuck to surfaces. Haddock wrote that the room had not looked clean since it opened. In the matter of losses, Haddock contested Shurtleff's method of counting books and produced his own tally, showing very little loss, with a volume or two showing up in a professor's room. Shurtleff had also complained that Haddock allowed students into the Library unaccompanied by the Librarian or any other faculty member. Here Haddock's defense begins to sound a bit petulant, but it illustrates a dilemma that surely had been shared by previous incumbents. The Library was but one of Haddock's many responsibilities; if he could not at a given time leave his other duties, he preferred to permit such unsupervised use rather than deny access completely. The conflict between his view of the lesser importance of his Library position and of the value of Library access, however limited, is clear:

It is an evil to allow anybody access to the Library without the Librarian, but it seems to be an evil incident to the system, that provides only for an occasional opening of the Library, by a person whose principal duty is elsewhere.

Haddock also noted that there had been no previous complaints about the Library, and that as a faculty member he valued his association with the College; he had “no interests to serve, in the destruction of its property.” Although the resolution of the conflict

The collection was considerably enhanced in 1852 by two substantial donations. Dr. George C. Shattuck gave $2000 for book purchases (in addition to the $7000 he donated for the construction of an observatory), and Professor Shurtleff added $1000, also for book purchases. Both donors stipulated that these books were to be used by the faculty only. The records are unclear concerning the donors' motivation—were they hoping to purchase books of advanced scholarship that would be of little use for students, or were they merely afraid that student use would result in loss or mutilation? Whatever the reasoning behind the limitations, the gifts, along with income from numerous contributions from the Parker family, did much to improve the quality of the collection.[47]

In 1828, the Trustees had requested—apparently not demanded—that the Librarian submit an annual report, primarily concerning finances.[48] If any were written before 1858, they have unfortunately been lost. After 1858, annual reports appear, with only a few gaps, through the early twentieth century. These reports are short, usually only a few pages in length, and consist mostly of lists of books added to the collection by purchase or gift. However, there is often enough commentary to give one an idea of the incumbents' views on the place of the Library in the College.

Hubbard had definite ideas about who should and should not be permitted to use the Library. He corresponded with colleagues at Harvard and Yale, and mentioned in his 1857–1858 report that a Harvard professor “informed me to day that students are not admitted to the alcoves.”[49] This and other reports cite the need for a catalog and better security; if anyone wanting a book could determine from a catalog that the

Hubbard took a dim view of students' ability to use the Library intelligently or responsibly. He frequently reiterated the need for security, as “preservation from actual robbery.” One student, during a vacation, had abandoned a trunk somewhere in settlement of a debt; the trunk's contents included some Library books. Other books had had their labels removed. His indignation of such cavalier treatment is often juxtaposed with his realization that “the real wants of every person should be met as far as possible.” Free access to the shelves would be of benefit to those of “cultivated minds,” from which company he clearly excluded students, at least those in the first two classes, whom he pictured as wandering aimlessly through the room, wondering, “Which book shall I take?" Even for the two upper classes, he recommended that the students take books “on permission of the instructors.”[52] President Nathan Lord, in his annual report for 1858–1859, observed that for one term the Library had been closed to all students, which did not seem to inconvenience them in any way:

The Library has been closed to students all the spring term. . . . From any thing that now appears, the Library might remain closed, with equal advantage, a much longer period.[53]

As usual, the students took refuge in the society libraries. In several letters to his father, Edward Tuck, Class of 1862, wrote of the College Library that “the College faculty have not yet seen fit to open it. . . . Our class is now purchasing donations for the [Society] Libraries.”[54]

Hubbard was, however, aware of the importance of the society libraries, but again with some ambivalence. He was annoyed that when some society members had not paid their taxes and were therefore kept from using the societies' books, there was “unusual pressure” on the College Library. But in a bit of an unconscious glimpse of the future, he said of the society libraries that “their best use is based upon the idea, that they are but parts of one system.” [55] Not all the students respected even the society libraries; even they had to resort to screens and locks to block direct access to the books.

In 1859, Dr. Henry Bond made a large donation of books including “English classics, "works on theology and American history, and a set of British parliamentary reports, with indexes.[56] For some reason, not noted in Hubbard's reports, these volumes were not made available for many years thereafter.[57] At a time when the most significant additions to the collection were gifts, Hubbard gave priority to caring for these items, realizing that donors frequently appeared at the Library asking to see their books, so they needed to be properly handled. He also mentioned one donor who wanted his books back—no reason supplied—and got them. Hubbard realized the importance of alumni as donors, stating that the Harvard librarian receives “books . . . from one in every 15, of the living graduates.”[58] Dartmouth's first alumni association had been formed in 1854,[59] but a specific effort to acquire works published by alumni was not begun until 1872.

In having to set priorities in caring for the collection, Hubbard noted on several occasions that not only could he not do everything at once, there was a “growing disproportion of pay & labor,” the Librarians' salary having been set in earlier times when there were far fewer books to deal with, and when there was less correspondence and

In several reports Hubbard mentions a collection of Congressional and other United States government publications. The federal depository program was still many years in the future, but the College was making a concerted effort to acquire these valuable primary sources, which apparently were distributed by the New Hampshire State Library. At one point these government works were not received as expected, and Hubbard felt it necessary to obtain “permission of proper authority” to go personally to the New Hampshire State House in Concord to retrieve them from the attic, where they had been left and forgotten. Hubbard acknowledged the good offices of an alumnus, Charles Reid, Class of 1835, who had become Librarian of the State of Vermont, in obtaining documents from that state—and regretted that the Library did not have a good similar collection of New Hampshire publications.[61]

Hubbard was a professor of chemistry, and before his appointment as Librarian, he had noted the deficiencies of the College's facilities in science.[62] In 1851 the Chandler School of Science and the Arts had been founded by the will of businessman Abiel Chandler. The complex relationship of the Chandler School to the College is beyond the scope of this essay, but as a scientist Hubbard took an interest in it and spent some time in its library. In the early 1860s the collection of scientific and technical material was greatly improved by a major donation from Colonel Sylvanus Thayer, Class of 1807, of books, maps, and related materials in engineering.[63] Believing that the contents were beyond the understanding of the undergraduates, Thayer stipulated that the books and other material were to be used by graduates and faculty only. The collection provided valuable support for the School of Civil Engineering at Dartmouth that Thayer endowed several years later.[64]

Hubbard resigned his Library position in 1865 and was succeeded by Charles Augustus Aiken, an alumnus of the Class of 1846 and the son of John Aiken, who had been Librarian from 1820 to 1822. His tenure was brief; he soon left to take teaching positions at other institutions, most notably the Princeton Theological Seminary, and he left no report of his activities. He was succeeded by Professor Edwin David Sanborn.[65]

Sanborn, Class of 1832, had a long and distinguished career at the College, spanning the administrations of three of its presidents. He held many other positions, formal and informal, besides that of Librarian, and also served in the state legislature. With his “forceful nature” he was well known and respected both on and off campus, “probably the most outstanding member of the faculty” at the time.[66] At this time the College found itself on a firm footing after the hard times of the previous half–century. There was extensive growth both in enrollment and physical plant.

Not all of Sanborn's annual reports survive, but those that do show a change in attitude from that of his predecessors regarding the content and care of the collection. His report for 1869–1870 has been frequently quoted; it begins, “the Librarian of the college, this year, submits a report in which there is nothing to be reported.” Four pages of “nothing” follow. “Nothing,” to Sanborn, was a result of very few books' having been purchased in the past year, and an indictment of the preponderance of outdated books on the shelves. As a professor of Latin, he certainly didn't believe that a book was outdated just because it was old, but he was distressed that the Library held no “Irving, Cooper, Hawthorne, Emerson, Lowell,” or other contemporary authors. American literature was coming into its own as the country matured; Sanborn wrote that “If students are limited to the books we possess, they cannot become acquainted with authors, whose names are as familiar to the reading public as household terms.” He also firmly believed that the College Library should supply archival material about the institution's history; there was “literally nothing illustrative of its own history, but the ‘Dartmouth Case' and a few pamphlets, written by Eleazar Wheelock, regarding Moor's school.” Hubbard had previously noted that there were boxes of papers on the Supreme Court case, lying around on the Library floor, virtually unusable, like the newspapers “lying, in wild confusion,” in the Northern Academy room. The secretary of the Alumni Association had had difficulty in obtaining information on College history to use in the recent centennial celebration; Sanborn noted that “of the early professors, almost no memorial is left, but their epitaphs; and their tombstones are crumbling to decay.” He hoped that the Trustees would authorize funds for the publication of a College history, although he conceded that the sale of the books probably would not recoup the costs.[67] His wishes were at least partially fulfilled when in 1872 Judge Nathan Crosby, Class of 1820, proposed to the Trustees that an alcove of publications written by Dartmouth alumni be established in the Library and supported it with a donation of $100.[68]

United Fraternity and Social Friends bookplates.

The most significant development during Sanborn's eight years as Librarian was the gradual merging of the society libraries with the College Library. For many years, the societies' importance in undergraduate life had been shrinking, as other activities, from athletics to musical groups, provided the students with a greater variety of extracurricular experiences. At the same time, there was a greater awareness on the part of students, society members or not, of the importance of libraries in general and the shortcomings of the College Library in particular. An article in the September 1872 issue of The Dartmouth, the student newspaper, expresses some of the opinion current at the time:

. . . the two most effective means of culture [are] books and instructors . . . why are we debarred from the enjoyment of . . . the free use of books? . . . the books are so much of the time inaccessible to the students; . . . books of reference are, practically, all the time inaccessible; and . . . there are in our libraries no conveniences for writing. The College Library is open not more than one hour a day through the year, this hour being the one when the students are, or ought to be, at play on the Common.

The arrangement of the books was confusing, and existing lists or catalogs didn't help much; the student who was “fearful of exhausting the patience of the librarian, goes away empty–handed.” Books in all of the libraries had for many years been kept locked behind “expensive wire doors” that provided a “tantalizing view of the books.”[69]

The society libraries were still well maintained and expanded; eventually they became the only real reason for the societies' existence. Accordingly, in July 1874 the Social Friends and the United Fraternity voted “to place their respective libraries under the care of the [faculty].” The most important parts of the plan for unification included the appointment of a librarian, with his salary set by the Trustees, and three assistants; a periodicals reading room, with hours of opening to be decided by the Academical (Dartmouth) and Chandler departments; and access to the combined libraries for all students. Sanborn worked with the societies' librarians, notably Clarence Watkins Scott of the class of 1874, to effect the transfer of control (but not yet ownership) of the society libraries to the faculty. The records are unclear about why Sanborn felt he should relinquish control, but when the Trustees approved the merger, Social Friends librarian Scott effectively became the Librarian of the combined collections. The merger was expected to reduce “the waste of their earlier management” and to “provide for the prosperity of the library without materially drawing upon the funds of the college.”[70] Scott has been called the College's first full–time Librarian; he did not assume other responsibilities for several years. But he was assuredly the first Librarian to take office so soon after his own commencement. He later taught in several departments of the College, including English, political economy, and history. He has left us a brief history of the Library that stops with the 1874 merger; it may have been written shortly thereafter. One hopes that Scott acquired better research techniques in his later years as a historian—he listed John Smith as Dartmouth's first Librarian, consigning poor Mr. Woodward to oblivion.

For the next two years, Scott devoted his time to the details of integrating the separate libraries. He had been listed as “Librarian” beginning with the 1874–1875 Catalogue of the College, and the Trustees formally reaffirmed his appointment in 1876.[71] In that year, Scott also assumed teaching duties in the New Hampshire College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts, which had been established in Hanover in the 1860s. Scott's final report as Librarian, for the year 1877–1878, is indicative of the success of the new system; the Library was open thirty–three hours a week, and the expenses incurred were the same as “previous to the present arrangement.” At the time of the merger, the Social Friends' library held approximately 9520 volumes, and the Fraters' about 9200. A smaller collection of about 1200 from the Philotechnic Society, which had been chartered by Chandler School students, was also included in the merger. The total Library collection, including the College Library, amounted to about 54,600 volumes.[72]

In 1878 Scott was succeeded by Louis Pollens, a native of Switzerland and graduate of the University of Vermont, who had been appointed an instructor in French in 1877. At the time of his being voted Librarian, he was also appointed Professor of French and German.[73] From this time on, issues that had been raised from time to time by earlier Librarians become more persistent and pressing. As the Library grew larger in size, space became inadequate, and as the hours increased, it became harder to manage as a part–time occupation. The merger agreement had stipulated assigning three students to act as assistants to the Librarian. The assistants would be paid a total of $100, part of which would be the amount of his room rent. Scott's final annual report had listed a total of $1500 for salaries; Pollens's salary alone was to be $1500, but that amount included compensation for his teaching responsibilities.

The need for larger—and especially fireproof—accommodations became ever more obvious. Fire had always been a risk; in 1822 the Trustees had requested ladders for escape from Library rooms.[74] In the early days the Library rooms were not heated, but Reed Hall was also a student residence, and even the staunchest advocate of New England hardiness would not have denied students heat in their lodging. Even after the installation of steam heat and gas lighting, students used oil lamps in their rooms, contrary to College rules. Pollens encouraged stricter enforcement of the ban, and in 1881 a Trustees' committee on the Library recommended that no students be allowed to room in Reed Hall. Pollens made reference to a disastrous fire at Amherst and feared that Dartmouth's library could similarly be “swept out of existence.”[75]

Pollens's reports show that the merging of the separate libraries did not always go smoothly. A major rearrangement was necessary so that books on any particular subject from the individual collections could be brought together in a single location. He worked on preparing a catalog but thought printing it would be a waste while books were constantly being shifted from one place to another because of space problems; he could not designate a permanent shelf location for any particular book. He made mention of the alumni collection by name, referring to it as the Alumni Alcove, a designation that survived for many years. With greater circulation—averaging about sixty per day in 1878–1879— there was need for a better system to track and recall books out on loan. He asked for a fourth assistant, preferably from the junior class, so that the student would have two years to become familiar with Library operation.[76] He proposed what might today be called a reserve system, whereby books required for courses could be kept in a single room and not circulated. It would be nice to say that a Dartmouth Librarian invented the reserve system, but Pollens indicated that he had seen such a system in operation at Harvard.[77]

In 1879 the Faculty turned over control of the society libraries to the Trustees. The Faculty Committee on the Union issued a formal statement approving this transition and expressed the hope that the increased efficiency of a unified collection would make it possible to heat Reed Hall “without drawing upon the College Treasury.”[78] When opening hours were increased, apparently even the stoic librarians realized that some heat was needed, fire risk notwithstanding; and if students were no longer rooming in Reed, there would have been no other heat in the building.

The 1870s were a period of transition in both higher education and the emerging field of librarianship. Many of the colonial colleges, as well as more recently–

Thirty thousand books well classified, thoroughly catalogued, easily accessible to the student, are of much more value than a hundred thousand, disorderly piled up in hidden and inaccessible corners.[80]

An admirable sentiment—and one that says much about the condition of the Library at the time. In addition to the rearrangement and cataloging of the books, he hoped to make both Dartmouth students and faculty aware of the collections:

It would be very helpful to all interested in the Library—and who is not?—to print annually or semiannually a list of new books with notes and such other matter as might fitly be added.[81]

He also hoped to make Dartmouth's Library more widely known in the academic community by exchanging such publication lists “among the larger and more progressive institutions in the country.” Progress was hindered by lack of space and by Pollens's other responsibilities. He cites the “chaos” of the Library's “Working Room” and the “lamentable death” of a professor of Greek, which “threw the burden of instruction in Grammar upon the Librarian.”[82]

For some time the Trustees had been considering a plan to convert the gymnasium into a space for the Library. The gymnasium's donor, George H. Bissell 1845, was not opposed to the plan, as long as the gym could be given new accommodations. However, this plan was never carried out. The College was also in need of a new chapel, and in 1883 Edward A. Rollins, of the Class of 1851, offered $30,000 for a chapel, if the College could also raise $60,000 for a library. This was a large amount to raise, and despite appeals to alumni, the College had not raised the required amount

The Library staff in 1883. Librarian Pollens is wearing the beard.

The library building, to be called Wilson Hall, was designed by Samuel J. F. Thayer of Boston, and constructed of red brick, with sandstone trimmings.[84] There were to be four levels of book stacks, two reading rooms, a reference room, and a picture gallery; the building was fireproof, and fitted with steam heat and electric lighting. In June of 1884 the cornerstones of both Wilson and Rollins Chapel were laid, with great ceremony. President Bartlett and the Reverend Henry Fairbanks, secretary of the Building Committee, made speeches. At the site of the future Wilson Hall, Trustee (and later President) William Jewett Tucker, Class of 1861, was proud that Dartmouth was keeping pace with several of the other colonial colleges, located in more populous areas and growing into true universities:

The Library of Dartmouth College has always held an honorable place among the general libraries of the country, and among college libraries it has kept the fourth place.

From an accumulation of books it has become an organism . . . The College Library is not a repository, but a workshop. . . . The average student is gradually learning the use of books.[85]

Professor Sanborn, retired since 1882 and quite ill, was in attendance. He said that Wilson's gift had given Dartmouth “new courage to labor for the progress of sound learning in our land.”[86]

Wilson Hall was ready for use just barely before the dedication ceremony, set for June 14, 1885, during Commencement Week. The shelves had not been finished until a week before the scheduled opening. Moving the books from Reed to Wilson was reminiscent of the hasty move from Dartmouth Hall to Reed back in 1840. President Bartlett called for volunteers, and a kind of book brigade was set up. Students working in pairs carried trays of books to the new Library—after dusting them—and arranged them on the shelves; the move took four days.[87]

The dedication ceremony took place as scheduled, with prayers, music, and speeches. It is worth quoting at some length from the speech by Mellen Chamberlain, Class of 1844, for many years a supporter of the Library with donations of both books and money. Chamberlain's remarks made note of the transformation of the Library from one that had been “ample for our purposes . . . but I fancy the accomplished librarian found his duties neither arduous nor largely remunerative.” A college library “has purposes of its own apart from those entertained by the institution with which it is connected. It is an education institution; it is a university in itself.” He had perhaps ambivalent views; the library should have a collection beyond course needs, but “discipline, rather than promiscuous reading, is the chief purpose of college life.” The College Library should be a repository for the history of the institution; Daniel Webster had made use of documents in the Library's possession in preparation for his argument before the Supreme Court. A copy of Webster's “small college” speech was in the cornerstone. Just before the benediction, President Bartlett spoke in response to Chamberlain's speech. Dartmouth now had a new Library, “sooner than we expected and better than we dreamed.”[88]

Pollens resigned in 1886 to concentrate on teaching. His final report as Librarian covers the period of the move to Wilson. Circulation increased following the move. Pollens was apparently surprised by this, possibly because of continuing difficulty in access to the books. Rules for access were continually in flux at this time; students could not go directly to the stacks in the building but had to request books at the desk.[89]

The new Librarian was Marvin Davis Bisbee, Dartmouth Class of 1871 and a graduate of the Chicago Theological Seminary. He had been provisionally appointed late in 1886; the Trustees formally voted on the appointment in January 1887.[90] Although he was not a library–school graduate, it is probably fair to say that he was Dartmouth's first professional Librarian. He had some pastoral and teaching responsibilities, but of necessity he had to devote most of his working life to the Library. He instituted changes representative of modern principles of library management that

But first he had to bring some order out of the chaos resulting from the move from Reed to Wilson, which according to his first annual report was much worse than the conditions following the move in 1840. There was “considerable confusion, arising from the interregnum in the office of librarian, and the great disorder occasioned by the removal from Reed Hall"; pamphlets and newspapers were in “disordered heaps.” Pollens had spent considerable time and effort in trying to create a catalog, but Bisbee dismissed it as almost worthless; there was “not a card in the drawers fit for use.”[91]

For the next ten years at least, several themes recur frequently in Bisbee's reports. A major issue was student conduct in the Library. Perhaps he hoped that a new building would inspire improved behavior, as had happened with the new chapel, but he was to be disappointed. His first report noted that “some necessary bracing up in the matter of discipline was not popular at the time of course.” Some books had been stolen, and others defaced with “obscene drawings.” In subsequent years there was “considerable thieving and lawlessness.” [92] These remarks seem at variance with reminiscences of Bisbee, which certainly do not paint him as the curmudgeon he appears to be in some of his reports. He was known to have helped students who might have had to leave College to find ways to earn enough money to stay, and others came to “feel that they were a part of his family.” [93] He was sometimes referred to as “Pa” Bisbee. In other years, he was quite pleased with the “quiet and pleasant” atmosphere, and when hours in the Reference and Reading Rooms were increased, the students' “conduct has been unexceptional," and there was “little disorder,” despite the lack of an attendant in the Reference Room.[94]

Indeed, Bisbee's relations with students, particularly freshmen, show that Dartmouth may have been a bit ahead of the times in recognizing that as libraries were becoming larger and more complex, students needed more help than simple printed catalogs to find what they needed. Bisbee occasionally met informally with freshmen, asking them what they were currently reading, and offered a bibliography course, for freshmen and some juniors, and individual, private instruction.[95] A description of his junior elective course in bibliography might give pause to reference librarians accustomed to presenting just one hour–long instruction session to a class. Bisbee's course “was conducted on the plan of securing the largest amount of actual handling of books.”

Third-floor stacks in Wilson Hall, 1885.

Each student prepared a list of books on his topic. The following weeks required that the students become familiar with important reviews, magazines, and publications of the Smithsonian and state historical societies; they then studied “the early universities, the early printers of Venice, Paris, Holland, and Germany, great critics, and special collections. . . . Indirectly, the instructor, by means of lectures, illustrated as far as possible, covered the field of the general subject, the evolution of books.”[96] In both his published writings and annual reports, he recognized that “modern methods of instruction” were requiring more extensive use of books besides assigned texts, stating—probably over–optimistically—that “The day of the single text–book is over.” [97] He cites President Eliot of Harvard on the library as “the very core of the university considered as a place of instruction.” [98] Bisbee later became an advocate of open stacks.[99]

In the later nineteenth century, along with adopting the seminar system of teaching for graduate or small undergraduate elective courses, many academic libraries saw parts of their collections withdrawn to be placed at the disposal of the various teaching departments. The faculty of the department controlled access to the books. Bisbee made a case for locating these “departmental” libraries in the central Library. He was not opposed to having the books relevant for a particular course kept together and separate from the main collection; he just thought such a subcollection would be more useful to the students if it were located adjacent to the reference and reading rooms.[100] Eventually the departmental libraries, although located outside Wilson, were brought into “closer relations with the central library,” although exactly how this was accomplished is not stated. Echoing Pollens many years before, Bisbee cited the Social Friends' classical collection as an early example of the departmental library, considerably predating Harvard's.[101]

Improving the catalog was another of Bisbee's priorities, and another proof that he was bringing the best of modern thinking on library management to Dartmouth. Catalogs in most libraries had until fairly recently been nothing but lists of titles. When a collection approaches 110,000 volumes, or even more, trying to find something specific from such a list is no more efficient than randomly looking at shelf after shelf. By 1893, Bisbee had begun the task of completely reclassifying the Library, including producing a card catalog that provided a subject approach, as well as author and title, to the collection.[102] Bisbee's system was modeled after that of library pioneer Charles Ammi Cutter, whose work was considered at the time the ultimate in scientific library practice. It worked well for the collection for many years, but became a major source of confusion in the 1960s. The records do not indicate how much of the actual cataloging was done by Bisbee himself. By 1902 the library was subscribing to a service of the Library of Congress that supplied catalog cards. The Dartmouth cataloger, whether librarian or student assistant, still had to write or type the call number on the cards, but not having to produce a set of cards for each book was a welcome time–saver; Bisbee wrote that “no library can profitably continue to write its own catalogue.”[103]

In his annual reports, Bisbee justified his requests for appropriations by increases in the size of the faculty and number of academic departments, with related increases in “scholarly work . . . the place of the library in educational work is growing in importance.” A Dartmouth student, James Gerould, Class of 1895, prepared in association with Bisbee a “Bibliography of Dartmouth College” that was to be “printed in the

Some of the early histories of the College were published at this time, using documents and records held by the Library. Before the construction of Wilson Hall, records, manuscripts, and publications relating to College and Hanover history had been “housed in various locations on campus and in private homes.” [106] The new building provided space where this material could be held in a single and accessible location; the collection later became known as the College Archives. Bisbee's reports record noteworthy additions, particularly Webster manuscripts, to the archival collection.[107]

A related collection, the Alumni Alcove, also found a home in Wilson. The volume of publications by Dartmouth alumni had grown steadily since Nathan Crosby's initial proposal in 1872. The subject matter encompasses theology, law, literature, and history; the collection shows “the wideness of the interests of Dartmouth graduates, the soundness of their instruction, and the vast range of their influence.” [108] The Library no longer attempts to collect all publications by Dartmouth graduates; the alumni books are still housed in Special Collections in the new Rauner Library.

The Library had improved dramatically from its earliest days, especially with the assimilation of the society libraries and the construction of a thoroughly modern facility. Yet Bisbee still worried that without an increase in resources to keep up with the longer hours and greater use of both circulating and reference books, the College Library would fall “behind others of our class.”[109] For many years Bisbee had had no help except from student assistants. He noted that

the librarian is now responsible for nearly the full work of an instructor. In view of this fact, some larger provision for assistance in the library would seem to be necessary.[110]

And again:

The library is feeling a steadily growing pressure to fill a larger place in the work of the college, and the librarian ventures to express the hope that the Trustees

will consider favorably the need of increased resources as rapidly as they may find it convenient.[111]

By 1907, a full–time cataloger was on the staff. A reference librarian was about to leave for another job, and Bisbee expressed to the Trustees the need for an “efficient and permanent head of this most important department.” Harold Goddard Rugg, Class of 1906, was by then on the staff, working with the collection of newspapers formerly belonging to the Northern Academy, which had disbanded in 1903. In the following year, a new reference librarian had been hired, and Bisbee commented on the Library's “unusual smoothness and efficiency, due in part at least to increased permanence of the force.” [112]

The years of Bisbee's administration formed a significant turning point in the history of the College Library. Bisbee became Librarian before professional degrees in librarianship were commonplace, but his management of the Library reflected his awareness of trends in academic librarianship throughout the country. He was granted a leave of absence in 1900 to study “the latest methods of library administration in Europe and America.”[113] He was also the last Librarian to have both teaching and pastoral responsibilities at the College. Dartmouth was then still a fairly small institution, and Bisbee surely had more personal involvement with both students and faculty than would be possible today.

From the founding of the College in 1769 to the final consolidation of the libraries in 1903,[114] the function of a “library” in the College evolved slowly from a small collection of specialized or archaic books with limited access and availability to a large collection of books, both for reference and borrowing, on a wide variety of subjects. A time–traveling student of 2002 could walk into the Wilson Hall of 1890 and recognize it instantly as a college library—an old–fashioned one, to be sure, with no computers or microforms or photocopiers—but a library nonetheless. The same student could walk into Mr. Woodward's home in 1774 and admire the collection of “very good books” but would probably not call it a “library.” From the turn of the century onward, change would come with sometimes dizzying speed, but the role of the Library as an enterprise central to the College's educational mission was firmly established.

For a year after Marvin Bisbee's retirement in 1910, there was no designated College Librarian. The circulation librarian, as ranking member of the staff, was nominally in charge, but ultimate responsibility for the Library rested with the President of the College.[115] In late 1911, the Trustees chose Nathaniel Lewis Goodrich, a graduate of the New York State Library School, to be Mr. Bisbee's successor. His duties and salary were to begin in January 1912. Goodrich's tenure, from 1912 until 1950, is the longest in the Woodward Succession[116] and covers an unparalleled array of changes both in the College and the country. In his thirty–eight years as Librarian, Goodrich saw the Dartmouth Library through two world wars, a depression, several major changes in the College's educational philosophy and curriculum, and, most significantly, the construction of Baker Library.

Under President Tucker's administration, from 1893 to 1909, the College had grown in both size and reputation, so much so that Tucker was said to have created the “New Dartmouth.” Its students came from all over the country, alumni clubs were becoming better organized and influential, and the curriculum had evolved from a narrowly–prescribed set of courses through a somewhat haphazard system of electives to a more structured program of both required courses and electives, but with a broader range of courses available. By 1912, when Goodrich became Librarian, Wilson Hall, dedicated with such pride and ceremony only a few decades past, was already being perceived as inadequate to meet the needs of faculty and students. Near the end of his nearly forty years as Librarian, Goodrich recalled that upon taking office he had

endeavored to sense the needs of the faculty and students, and the wishes of the administration, and to satisfy them as far as conditions permitted. Beyond these

basic requirements I had two chief aims; to create in the Library an atmosphere of cheerful helpfulness, and to provide the books and periodicals which would keep faculty and students in touch with current affairs as well as give them recreational reading.[117]

Goodrich devoted the first decades of his tenure to dealing with, and improving, those conditions.

The Faculty Committee on the Library, of which the Librarian was a member and sometime chairman, brought up a number of issues that would recur in many subsequent debates about the College's library facilities. Some had turned up in earlier years. A 1906 committee report reaffirmed Bisbee's desire that the departmental libraries should eventually become part of the College's collection: “Centralization of book collections is the policy of the library.” The Physics Department had actually asked for some supervision from the “main” library, although the collection was housed in the department's building and not Wilson. The committee recommended that the departmental collections should be cataloged. A new library, should one ever be built, should include a plan for “extensive enlargement"; should provide for special collections and a vault for irreplaceable items; should contain rooms that promoted recreational reading; and should have a limited number, if any, of seminar rooms or classrooms. Location “removed from the center of college activities . . . would provide an excuse for non–use;” the north end of the campus should be the “active center of the college.”[118]

Discussion of new library facilities was curtailed by the outbreak of war in Europe and the subsequent involvement of the United States, and other library projects were similarly affected. The system of cataloging and classification that in Bisbee's time had been such an advance was proving unworkable as the collection increased, and Goodrich wanted to recatalog the collection according to the Dewey Decimal System. It was to be a monumental undertaking, and the plan was postponed until the end of the war. Although enrollment had dropped, the College was able to keep functioning, but because of reduced staff and funding, projects like reclassification necessarily were put on hold. Other effects of the war were felt in the Library. The Faculty Committee on the Library made note of the difficulty in getting books from Europe, especially Germany. The Librarian went on leave of absence to serve in the Army, leaving an acting librarian in charge. The Library patriotically subscribed to Stars and Stripes, the Army newspaper.[119]

The unsettled state of Europe after the war resulted in a “price débâcle” that allowed American institutions to purchase scholarly works that would have otherwise

The Faculty Committee resumed its discussion of library problems, and in 1920 issued a report entitled “A Library Building for Dartmouth College.” The recommendations in the report differ only slightly from those mentioned in the pre–war debates. Many of the issues were stated in the form of questions:

Are we to plan a College or a University library? . . .

Is the encouragement of recreational reading a library duty? . . .

Are we to sacrifice ‘atmosphere' to administrative efficiency?[121] . . .

Issues concerning the scope of the collections did not figure prominently in these discussions, but it is interesting to note that the gift of some miniature symphonic scores brought some depth to a previously–neglected area. Another suggestion was that the library should develop a collection “in out–of–door sport.” The faculty's decision to offer courses in evolution and citizenship also affected choices in books ordered for the collection. As the College added new areas of study, it became harder for both faculty and Librarian to keep up with publication in so many fields. The committee noted that an “ideal library would have on its staff a number of assistants, perhaps one from each ‘divisional' field, whose chief work would be keeping in touch with the literature.” Funds were to be distributed by department.[122] This idea was developed more fully much later when the Library added several selection officers to the staff.[123]

In May of 1925 the Dartmouth faculty adopted a new plan for the organization of undergraduate study that brought further importance to the discussion of Library issues. A 1923 faculty committee had reported that “higher standards should be set in most courses . . . teaching should be more stimulating.”[124] The Committee on Educational Policy had been “startled out of its complacency" by a subsequent report from a retired professor that

American undergraduates, not only at Dartmouth, but in all American universities and colleges, were doing no work, that they graduated without knowing anything, that they graduated without even wanting to know anything, and that the responsibility for this state of affairs was not theirs, nor could it honestly be attributed to the disproportionate interest in athletics.[125]

President Hopkins subsequently charged Professor Leon Burr Richardson, Class of 1900, with undertaking a study of universities and colleges both in the United States and Europe, and in an unprecedented move, sought undergraduate opinion in the form of a committee made up of the most able men in the senior class. The students recommended classes modeled after “the Tutorial System at Harvard” and a major field of study demonstrating “reasonable mastery of a subject” as shown by a “general comprehensive examination.” The students recognized that such a program would “require an increase in library facilities.”[126]

Both the student committee report and Richardson's study,[127] which emphasized the value of independent work once a general core of knowledge had been acquired, received wide notice in the press. The Dartmouth faculty approved the new system, to take effect with the Class of 1929. The principal features were that the student, in the first two years, should gain “a general familiarity with the various departments of knowledge,” and that in the last two years should “devote himself to the study of some one department of knowledge so that it may no longer be said of him that he has merely a ‘smattering’ of everything, but no thorough comprehension of anything.” The students were to take a comprehensive examination in the major field. The new plan made provision for an honors program of individual study for exceptional students.[128]

With a new curriculum emphasizing independent reading, at least for about twenty percent of the two upper classes, the inadequacies of Wilson became even more apparent. The student body in 1925 was about five times larger than in 1885, when Wilson was built, and the number of courses offered and book collections to support them had similarly increased. There was such a shortage of space that books were stored in basements in Wilson and other buildings; the disarray made it difficult to find a book when needed. A committee member noted that Wilson was “a sad old library, but the books are used.”[129] At the same time, a description of the Library in relation to the College's athletic facilities was becoming distressingly commonplace. In 1925 a debating team from Oxford University visited Dartmouth, and one of the debaters allegedly said

that he had a special interest in coming to Dartmouth because he had heard that the College had the largest gymnasium and the smallest library of any college in America.[130]

Baker Library under construction, 1927.

This diatribe appeared in a number of versions, sometimes merely that Dartmouth's gym was larger than its Library, without the invidious comparisons. Regardless of its literal truth, in any of its incarnations the idea was widespread enough to drive the Trustees and President Hopkins to speed up the ongoing consideration of a new library building.

At the 22 October 1925 meeting of the Board of Trustees, Lewis Parkhurst, Class of 1878, recalled an address by President Tucker some twenty years ago before a group of Boston alumni, in which he cited several goals of his administration—a new gymnasium, an administration building, and a library—and that Dartmouth was “still without a library,” the other buildings having been completed. It was Parkhurst's opinion that the delay was fortunate, since the College's needs had changed so dramatically in the succeeding years that building an addition to Wilson at that time would have been “like throwing money away.”[131] In building the New Dartmouth, which included adding a graduate school of business to the already existing medical and engineering schools, President Tucker had had to allay fears among many alumni that the College was slowly turning into a university, although it probably would have to become more than a “small college.”[132] In its deliberations about Library issues more than twenty years later, the Trustees affirmed that Dartmouth had “no expectations of becoming a university or any pretensions in that direction.”[133] The Trustees unanimously voted that they “take measures for the immediate construction of a library building” and that “the President appoint a special committee” to study all aspects of the proposed venture.[134]

Construction was not, of course, immediate. Members of the Faculty Library Committee and the Special Library Committee spent a large portion of their professional lives over the course of two years discussing problems and opportunities. They spent considerable time trying to ensure that any new library would not outgrow its usefulness with the regrettable speed that Wilson had. Professor Charles N. Haskins, of the faculty committee, visited Vassar and learned from its librarian that that college had had a similar experience; Vassar had built a new library twenty years ago, and twelve years later, it needed enlarging. The Vassar librarian recommended the inclusion of a staff room, staff offices, and a map room.[135]

Goodrich met with members of the student society Palaeopitus, who voiced a concern that continues to this day: the need for study space in the Library, because of