Hanover, New Hampshire : Dartmouth College

Copyright Trustees of Dartmouth College

PUBLISHED IN COMMEMORATION

OF THE ONE-HUNDREDTH ANNIVERSARY

OF HIS BIRTH • MARCH 2, 19O4-2OO4

Edited by Edward Connery Lathem

together with an introduction

by President James Wright

HANOVER • NEW HAMPSHIRE

Dartmouth College

This publication has been sponsored by

the WILLIAM L.BRYANT

FOUNDATION

established by William J. Bryant

Dartmouth Class of 1925

The text of the reminiscence is that

originally published in the April 1976

number of the

Dartmouth Alumni Magazine.

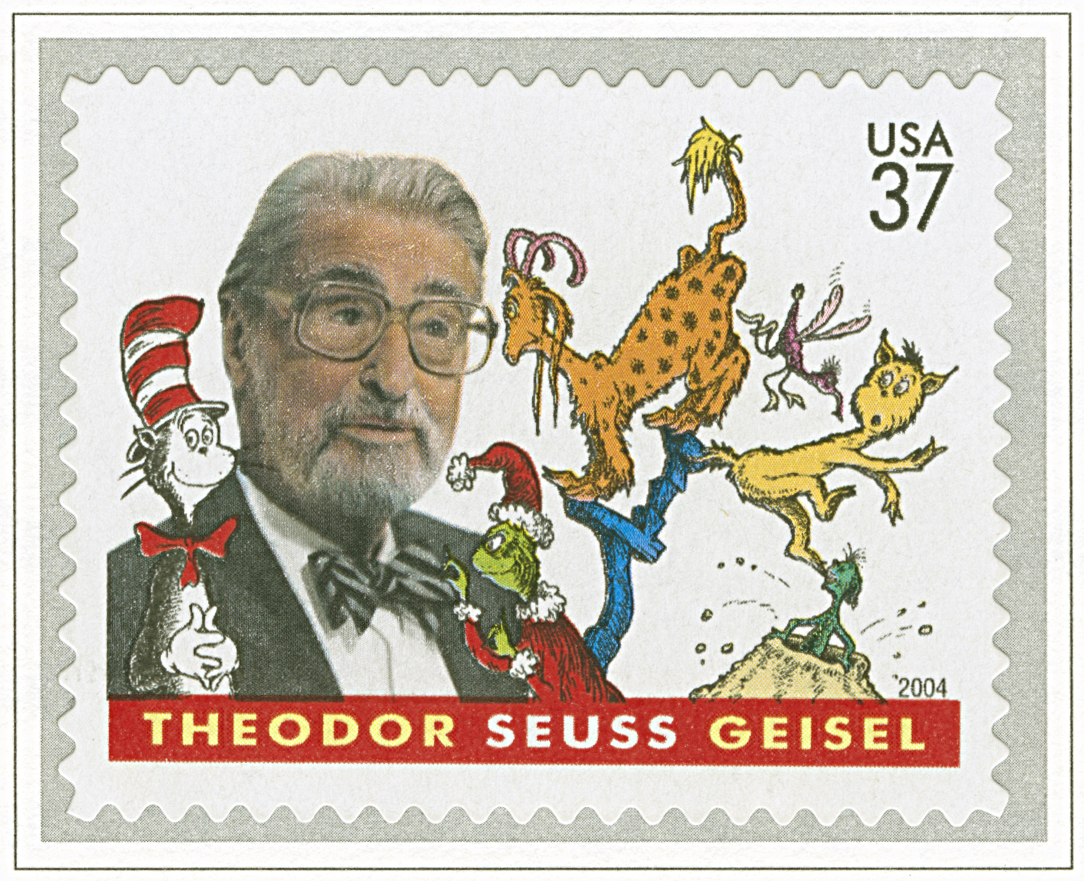

TITLE-PAGE ILLUSTRATION

U. S. Postal Service commemorative

Theodor Seuss Geisel stamp issued

March 2, 2004 at La Jolla, California

"Dr. Seuss" signature reproduced

courtesy of Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P.

IT IS WITH particular delight that I welcome readers

to The Beginnings of Dr. Seuss. At Dartmouth we

take special pride in this extraordinary genius who

graduated from the College in 1925. Theodor Seuss

Geisel — Dr. Seuss — brought joy to millions.

Ted Geisel came to Dartmouth uncertain as to

his path in life. Happily, however, he discovered and

began developing here a rare talent to engage and

entertain, to enlighten and instruct — a talent that

would in subsequent years serve to enchant a broad

range of readers through his wonderful drawings and

inspired stories.

It was at Dartmouth, as he reveals in the pages

that follow, that he "discovered the excitement of

`marrying’ words to pictures." He said:

"I began to get it through my skull that words

and pictures were Yin and Yang. I began thinking that

words and pictures, married, might possibly produce

a progeny more interesting than either parent."

And, with typical modesty, he went on to say:

“It took me almost a quarter of a century to find the

In recognition of his great accomplishments

and in testimony to our pride in "the distinction of a

loyal son," the College awarded Mr. Geisel an honorary

degree in June 1955. In 2000, I had the personal,

as well as official, pleasure of bestowing an honorary

doctorate upon Audrey Stone Geisel. In the citation,

I said to her:

"Mr. Geisel himself made abundantly clear your

important role in encouraging and enhancing his creativity.

You sustained him in the most profoundly

productive interval of his long career."

I went on to speak of her exercise of "effective

stewardship over the Seuss legacy” and of the munificence

of her actions in support of education, literacy

programs, and health care. And the citation ended:

"Now, on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the

graduation of your late husband's class, his College

believes —a conviction we are confident both Dr.

Seuss and Dr. Theodor Geisel would enthusiastically

share —that you, madam, their partner, also eminently

deserve to bear, with them, the distinction of

doctoral tide, as well as membership in the Dartmouth

This volume contains Theodor Geisel’s own

reflections on his early career —from high school

through the publication in 1937 of And to Think That

I Saw It on Mulberry Street, his first of what were to be

many immensely successful books. The text is drawn

from tape recordings made in 1975, just in advance of

the fiftieth reunion of the Class of 1925, which occa-

sion featured a major Geisel/Seuss exhibition that

was mounted in Baker Library.

The volume is now issued in tribute to Theodor

Seuss Geisel as part of Dartmouth's celebration of his

centennial — at the close of the year that has marked

the one hundredth anniversary of his birth. Its exis-

tence owes much to the vision and editorial skills

of Edward Lathem, Bezaleel Woodward Fellow and

Counselor to the President, Dean of Libraries and

Librarian of the College, Emeritus. He has brought

many volumes to publication during a distinguished

career — but few perhaps so satisfying to him as this

one, because of his long friendship with Mr. Geisel.

J.W.

December 2004

is of course a pseudonym, one known

is of course a pseudonym, one known

to millions upon millions of adults and children alike,

in the United States and throughout the world.

It derives from the middle name of author-artist

Theodor Seuss Geisel (Dartmouth 1925), and any telling

of the story of "Dr. Seuss" must involve a tracing,

also, of the career of Theodor Geisel himself.

Both born and raised in Springfield, Massachusetts,

he attended Springfield's Central High School,

where among his special extracurricular concerns was

the student newspaper, the Central Recorder, for which

he did articles, verse, humorous squibs, and occasional

cartoons, as well as serving as one of the paper's editors.

At the conclusion of his high school years he,

along with a large number of others from Central

High, entered Dartmouth, apparently because of the

influence of Edwin A. Smith, a 1917 graduate of the

College.—

"The reason so many kids went to Dartmouth at

that particular time from the Springfield high school

was probably Red Smith, a young English teacher

who, rather than being just an English teacher, was

one of the gang — a real stimulating guy who proba-

bly was responsible for my starting to write.

"I think many kids were excited by this fellow.

(His family ran a candy factory in White River Junc-

tion, Vermont. I remember that.) And I think when

time came to go to college we all said, 'Let's go where

Red Smith went.'"

Accordingly, in the autumn of 1921, Geisel headed

for Hanover, some hundred and thirty miles up the

Connecticut River from Springfield.

And what was to prove, as viewed in retrospect,

especially a stimulus to him at Dartmouth?—

"Well, my big inspiration for writing there was

Ben Pressey [W. Benfield Pressey of the Department

of English]. He was important to me in college as

Smith was in high school.

"He seemed to like the stuff I wrote. He was very

informal, and he had little seminars at his house (plus a

very beautiful wife, who served us cocoa). In between

sips of cocoa, we students read our trash aloud.

"He's the only person I took any creative writing

courses from ever, anywhere, and he was very kind

and encouraging.

"I remember being in a big argument at one of

Ben's seminars. I maintained that subject matter wasn't

as important as method. (I don't believe that at all now.)

"To prove my point, I did a book review of the

Boston & Maine Railroad timetable. As I remember,

nobody in the class thought it was funny — except

Ben and me."

From the outset at Dartmouth, Freshman Geisel

gravitated toward association with the humor magazine,

Jack-o-Lantern.—

"That was an extension of my activities in high

school — and a lot less dangerous than doing somersaults

off the ski jump. I think I had something in

Jack-o-Lantern within a couple of months after I got

to college."

Jack-o-Lantern proved increasingly an object of

Geisel’s attentions throughout his four years in

Hanover, and at the end of his junior year he became

editor-in-chief. —

"Another guy who was a great encouragement

was Norman Maclean. He was the editor preceding

me. He found that I was a workhorse, so we used to

write practically the whole thing ourselves every

month.

"Norman, at the same time, was writing a

novel. And the further he got involved with his

novel, the less time he had for his Jack-o-Lantern. So,

"One night Norman finished the novel and

went out to celebrate. While he was out celebrating,

his boarding house burned down and his novel

burned up. Unlike Thomas Carlyle, I don't think he

ever rewrote it."

The general practice of Jack-o-Lantern was that

its literary content appeared unsigned, a circumstance

that renders it impossible to compile today

a comprehensive listing of Geisel's writings for its

pages. The author himself has only vague recollections

of what he in fact wrote for the publication, although

he does remember that certain contributions

were written jointly with Maclean, including ones

that came about in a singular fashion.—

"Norman and I had a rather peculiar method of

creating literary gems. Hunched behind his typewriter,

he would bang out a line of words.

"Sometimes he'd tell me what he'd written,

sometimes not. But, then, he'd always say, 'The next

line's yours' And, always, I'd supply it.

"This may have made for rough reading. But it

was great sport writing."

The art work included in Jack-o-Lantern was,

unlike its "lit," usually signed, and the magazine's issues

of 1921-1925 are liberally sprinkled with cartoons

bearing explicit evidence of having come from Ted

Geisel’s pen.

The 1920s were seemingly "the era of the pun,"

and many of the individual cartoons are found to

have involved puns or currently popular expressions.

Going back, now, over the pages of Jacko for his

undergraduate years, Geisel is rather stern in his

judgment of the cartoons that were included, and

particularly of those he himself drew.

In summing up his assessment he says:

"You have to look at these things in the perspective

of fifty years ago. These things may have been

considered funny then, I hope — but today I sort of

wonder.

"The best I can say about the Jacko of this era is

that they were doing just as badly on the Harvard

Lampoon, the Yale Record, and the Columbia Jester.”

During his student days Geisel also went into

print from time to time in another campus publication,

The Dartmouth, "America's Oldest College

Newspaper."—

"Whit Campbell was editor of The Daily Dartmouth

at the time. I filled-in occasionally and did a

few journalistic squibs with him.

"Almost every night I’d be working in the Jack-

o-Lantern office, and while waiting for Whit's morning

paper, across the hall, to go to press, we used to

play a bit of poker.

"Once in a while, if one of Whit's news stories

turned sour, we'd put our royal-straight flushes face

down on the table, rewrite the story together, and

then pick up our royal-straight flushes again — and

sometimes raise each other as much as a quarter.

"This did little to affect the history of journal

ism in America. But it did cement the strongest personal

friendship I made at Dartmouth."

There were two especially noteworthy aspects

of the extensive work Geisel did for Dartmouth's

humor magazine.

The first of these emerged during his junior

year, and he identifies it as having been in his undergraduate

period "the only clue to my future life." It

involved a technique of presentation, the approach to

a form for combining humorous writing and zany

drawings.—

"This was the year I discovered the excitement

of 'marrying’ words to pictures.

"I began to get it through my skull that words

and pictures were Yin and Yang. I began thinking that

words and pictures, married, might possibly produce

a progeny more interesting than either parent.

"It took me almost a quarter of a century to find

the proper way to get my words and pictures married.

At Dartmouth I couldn't even get them engaged."

The other particularly significant feature of

Geisel’s Jack-o-Lantern career relates to the spring of

1925, when apparently he first used the signature

"Seuss." The circumstances diat surrounded his employment

of the later-famous pseudonym, he outlines

as follows.—

"The night before Easter of my senior year there

were ten of us gathered in my room at the Randall

Club. We had a pint of gin for ten people, so that

proves nobody was really drinking.

"But Pa Randall, who hated merriment, called

Chief Rood, the chief of police, and he himself in person

raided us.

"We all had to go before the dean, Craven

The disciplinary action imposed by Dean

Laycock meant that the editor-in-chief of Jack-o-

Lantern was relieved forthwith of his official responsibilities

for running the magazine. There existed,

however, the practical necessity of helping to bring

out its succeeding numbers during the remainder of

the academic year.

Articles and jokes presented no problem, since

they normally appeared anonymously; thus, anything

the deposed editor might do in that area could

be completely invisible as to its source.

Cartoons, on the other hand, usually being

signed contributions, did present a dilemma; and it

was a dilemma Theodor Seuss Geisel resolved by

publishing some of his cartoons entirely without signature

and by attributing others of them to fictitious

sources.

The final four Jacko issues in the spring of 1925

contained, accordingly, a number of Geisel cartoons

anonymously inserted or carrying utterly fanciful

cognomens (such as "L. Burbank" "Thos. Mott

"To what extent this corny subterfuge fooled

the dean, I never found out. But that's how 'Seuss'

first came to be used as my signature. The ‘Dr.’ was

added later on."

In June of 1925, Ted Geisel finished his undergraduate

course at Dartmouth and prepared to embark

upon a further academic adventure. It was one

he had ardently desired to pursue, but it proved, in

the end, to have a slightly different route of approach

than he had anticipated.—

"I remember my father writing me and asking,

'What are you going to do after you graduate?'

"I wrote back, 'Don't you worry about me, I'm

going to win a thing called the "Campbell Fellowship

in English Literature" and I'm going to Oxford'

"He read the letter rather hurriedly. The editor

of the Springfield Union lived across the street from us

(that was Maurice Sherman; he was also a Dartmouth

man), and my father ran across the street and

said: ‘Hey, what do you know? Ted won a fellowship

"So, Maurice Sherman, being a staunch Dartmouth

man, ran my picture in the paper (I think it

was on the front page): 'GEISEL WINS FELLOWSHIP

TO GO TO OXFORD.' And everybody called up

my father and congratulated him.

"Well, it so happened that that year they found

nobody in the College worthy of giving the Campbell

Fellowship to. So, my father, to save face with

Maurice Sherman and others, had to dig up the

money to send me to Oxford, anyway."

In the autumn of 1925, Geisel entered Oxford as

a member of Lincoln College.—

"My tutor was A. J. Carlyle, the nephew of the

great, frightening Thomas Carlyle. I was surprised to

see him alive. He was surprised to see me in any form.

"He was the oldest man I've ever seen riding a

bicycle. I was the only man he'd ever seen who never

ever should have come to Oxford.

"This brilliant scholar had taken 'Firsts' in every

School in Oxford, excepting medicine, without studying.

Every year, up to his eighties, he went up for a

different 'First,' just for the hell of it.

"Patiently, he had me write essays and listened

to me read them, in the usual manner of the Oxford

tutorial system. But he realized I was getting stultified

in English Schools.

"I was bogged down with old High German

and Gothic and stuff of that sort, in which I have no

interest whatsoever — and I don't think anybody really

should.

"Well, he was a great historian, and he quickly

discovered that I didn't know any history. Somehow

or other I got through high school and Dartmouth

without taking one history course.

"He very correctly told me I was ignorant, and

he was the man who suggested that I do what I finally

did: just travel around Europe with a bundle of high

school history books and visit the places I was reading

about — go to the museums and look at pictures

and read as I went. That's what I finally did."

As an example of one factor contributing to the

stultifying atmosphere he encountered at Oxford, he

still has vivid memories of a don at the university

who had produced a variorum edition of Shakespeare

and who was chiefly interested in punctuational

differences in Shakespearean texts.—

"That was the man who really drove me out of

Oxford. I'll never forget his two-hour lecture on the

punctuation of King Lear.

"He had dug up all of the old folios, as far back

as he could go. Some had more semi-colons than

commas. Some had more commas than periods.

Some had no punctuation at all.

"For the first hour and a half he talked about the

first two pages in King Lear, lamenting the fact that

modern people would never comprehend the true

essence of Shakespeare, because it's punctuated badly

these days.

"It got unbelievable. I got up, went back to my

room, and started packing."

A notebook used by Geisel during his time at

Oxford has survived among his papers.—

"I think this demonstrates that I wasn't very interested

in the subtle niceties and complexities of

English literature. As you go through the notebook,

there's a growing incidence of flying cows and strange

beasts. And, finally, at the last page of the notebook

there are no notes on English literature at all. There

are just strange beasts."

This period, despite its academic frustrations,

"While I was at Oxford I illustrated a great hunk

of Paradise Lost.

"With the imagery of Paradise Lost, Milton's

sense of humor failed him in a couple of places. I remember

one line, 'Thither came the angel Uriel, sliding

down a sunbeam.'

"I illustrated that: Uriel had a long, locomotive

oil can and was greasing the sunbeam as he descended,

to lessen the friction on his coccyx. And I

worked a lot on Adam and Eve.

"Blackwell, the great bookseller and publisher,

was right around the corner from Lincoln, and I remember

I had the crust to go in there and ask them to

commission me to do the whole thing.

"Somebody took it into a back room and then

came back with it very promptly and said, 'This isn't

quite the Blackwell type of humor'

"So, I was thrown out. But I got my revenge

years later.

"I went to Oxford about twenty years later. I

went past Blackwell's and found the whole window

Clearly, the most important circumstance associated

with Ted Geisel’s interval at the University of

Oxford was his meeting there a young lady from

New Jersey named Helen Palmer.

A graduate of Wellesley College, Miss Palmer

had in the autumn of 1924 entered upon studies at

Oxford to complete her preparations for becoming a

schoolteacher back home in America.—

"She was a gal who was sitting next to me when

I was doing this notebook, and she was the one who

said, ‘You’re not very interested in the lectures.’ She

'picked me up’ by looking over and saying, I think

that's a very good flying cow.’

"It was she who finally convinced me that flying

cows were a better future than tracing long and short

E through Anglo Saxon.

"She was the one who convinced me that I wasn't

for pedagogy at all.

"On the other hand, she did complete the English

Schools that year; took her degree in English Lit.

This enabled her to get a job teaching English in the

States. This enabled us to get married."

Upon quitting Oxford, Geisel did engage

briefly in one final scholastic interlude, this time in

Paris.—

“At Oxford I went to a lecture (I was very interested

in Jonathan Swift) by the great Emil Legouis.

Although he was a Frenchman, he was the greatest

Swift authority in the world at that time.

"He talked to me at the end of the lecture and

began selling me on going to study with him at the

Sorbonne. And, after I left Oxford, I did so.

"I registered at the Sorbonne, and I went over to

his house to find out exactly what he wanted me to do.

"He said, ‘I have a most interesting assignment

which should only take you about two years to complete.’

He said that nobody had ever discovered anything

that Jonathan Swift wrote from the age of sixteen

and a half to seventeen.

"He said I should devote two years to finding

out whether he had written anything. If he had, I

could analyze what he wrote as my D.Phil. thesis.

Unfortunately, if he hadn't written anything, I

wouldn't get my doctorate.

"I remember leaving his charming home and

walking straight to the American Express Company

"There I proceeded to paint donkeys for a

month. Then, I proceeded with Carlyle's idea and

began living all around the Continent, reading history

books, going to museums, and drawing pictures.

"I remember a long period in which I drew

nothing but gargoyles. They were easier than Mona

Lisas."

And what of those months of junketing?—

"While floating around Europe trying to figure

out what I wanted to do with my life, I decided at

one point that I would be the Great American

Novelist. And so I sat down and wrote the Great

American Novel.

"It turned out to be not so great, so I boiled it

down in the Great American Short Story. It wasn't

very great in that form either.

"Two years later I boiled it down once more and

sold it as a two-line joke to Judge.”

Home once again in Springfield, Geisel lived

with his parents and began submitting cartoons to

national magazines.—

"I was trying to become self-sufficient — and my

Finally, a submission to The Saturday Evening

Post was accepted. It was a cartoon depicting two

tourists on a camel, and it appeared in the magazine's

issue for July 16,1927.

The drawing was signed simply "Seuss" by its

draftsman-humorist, resurrecting the pseudonym he

had used in the Dartmouth Jack-o-Lantern two years

earlier.—

"The main reason that I picked 'Seuss' professionally

is that I still thought I was one day going to

write the Great American Novel. I was saving my real

name for that — and it looks like I still am."

Actually, the Post in publishing his cartoon accorded

"Seuss" no pseudonymity whatsoever, for it

supplied the identification "Drawn by Theodor Seuss

Geisel" in a byline of type, right along the edge of the

drawing itself.—

"When the Post paid me twenty-five bucks for

that picture, I informed my parents that my future

success was assured; I would quickly make my fame

and fortune in The Saturday Evening Post.

"It didn't quite work out that way. It took

But success during the summer of 1927 in placing

something with The Saturday Evening Post was a

cause for great elation — and, moreover, for a decision

on the cartoonist's part to leave Springfield.—

"Bubbling over with self-assurance, I told my

parents they no longer had to feed or clothe me.

"I had a thousand dollars saved up from the

Jack-o-Lantern (in those days college magazines made

a profit), and with this I jumped onto the New York,

New Haven, & Hartford Railroad; and I invaded the

Big City, where I knew that all the editors would be

waiting to buy my wares."

In New York, Geisel moved in with an artist

friend from his Dartmouth undergraduate days,

John C. Rose, who had a one-room studio in

Greenwich Village, upstairs over Don Dickerman's

night club called the "Pirates Den."—

"The last thing we used to do at night was to

stand on chairs and, with canes we'd bought for that

purpose, play polo with the rats, and try to drive

"And I wasn't selling any wares. I tried to do so

phisticated things for Vanity Fair; I tried unsophisticated

things for the Daily Mirror.

"I wasn't getting anywhere at all, until John

suddenly said one day, 'There's a guy called "Beef

Vernon," of my class at Dartmouth, who has just

landed a job as a salesman to sell advertising for

Judge.

"'His job won't last long, because nobody buys

any advertising in Judge. But maybe, before Beef gets

fired, we can con him into introducing you to

Norman Anthony, the editor.'"

The result of the Geisel-Anthony meeting was

the offer of a job as a staff writer-artist for the humor

magazine, at a salary of seventy-five dollars per week

— enough encouragement to cause Ted Geisel and

Helen Palmer (who had been teaching during the

year since the completion of her Oxford studies) to

marry. The wedding took place at Westfield, New

Jersey, on November 29,1927.—

"We got married on the strength of that. Then,

"And the next week they instituted another fiscal

policy (I was getting a little bit worried by this time)

in which they dispensed with money entirely and

paid contributors with due bills. Due bills?

"Judge had practically no advertising. And the

advertisers it attracted seldom paid for the ads with

money; they paid the magazine with due bills. And

that's what we, the artists and writers, ended up with

in lieu of salary.

"For instance: a hundred dollars; the only way

for me to get the hundred dollars was to go down to

the Hotel Traymore in Atlantic City and move into a

hundred-dollar suite.

"So, Helen and I spent many weeks of our first

married year in sumptuous suites in Atlantic City —

where we didn't want to be at all.

"Under the due-bill system I got paid once, believe

it or not, in a hundred cartons of Barbasol shaving

cream. Another time I got paid in thirteen gross

of Little Gem nail clippers.

"Looking back on it, it wasn't really so bad, be-

"How can you file an income tax when you're

being paid in cases of White Rock soda?"

And where did the newlywed Geisels set up

housekeeping in New York?—

"Oh, we went to a place across from a stable in

Hell's Kitchen, on 18th Street.

"Horses frequentiy died in the stable, and they'd

drag them out and leave them in the street, where

they'd be picked up by Sanitation two or three days

later.

"That's where I learned to carry a 'loaded' cane.

It was about a three-block walk to the subway. If you

weren't carrying a weapon of some sort, you'd be sure

to get mugged.

"So, Helen and I worked harder than ever to get

out of this place. And we finally managed to move

north, to 79th Street and West End Avenue. There

there were many fewer dead horses."

"Seuss" work in Judge consisted not only of cartoons.—

"I was writing some crazy stories, as well. It was

Among these combination pieces, extending

the type of thing he had begun doing as an undergraduate

at Dartmouth, Geisel produced for Judge a

succession of regular contributions signed in a way

that brought his pseudonym into the final form of its

evolution.—

"I started to do a feature called ‘Boids and

Beasties.’ It was a mock-zoological thing, and I put

the ‘Dr.’ on the ‘Seuss' to make me sound more professorial."

At first the self-bestowed "Dr." was accompanied

by "Theophrastus" or "Theo." in by-lines and as

a signature for drawings, but with the passage of time

"Dr. Seuss" was settled on as the standard form of his

identification.

"Dr. Seuss" soon found his way into other magazines

of the day, besides Judge, including Liberty,

College Humor, and Life. He even teamed up, at one

point, with humorist Corey Ford in a collaboration

for Vanity Fair that was, in the end, to be abandoned

out of pure frustration.—

"I illustrated some stories for Corey Ford in

"The last thing I did with Corey was a spoof on

political cartooning in the 1890s — a Boss Tweed type

thing.

"The art director laid the thing out before I did

the drawings, and he insisted that my average picture

was to be nine inches wide and three-quarters of an

inch high. This caused Boss Tweed and me to roll

over in our graves.

"Corey and I remained good friends, but we

didn't work together after that."

An occurrence early in Geisel’s period of association

with Judge was to have a particular impact on

his subsequent career.—

"I'd been working for Judge about four months

when I drew this accidental cartoon which changed

my whole life. It was an insecticide gag.

"It was a picture of a knight who had gone to

bed. He had stacked his armor beside the bed. There

was this covered canopy over the bed, and a tremendous

dragon was sort of nuzzling him.

"He looked up and said, 'Darn it all, another

"With what? I wondered.

"There were two well-known insecticides. One

was Flit and one was Fly Tox. So, I tossed a coin. It

came up heads, for Flit.

"So, the caption read, ‘... another Dragon.

And just after I’d sprayed the whole castle with Flit!”

"Here's where luck came in.

"Very few people ever bought Judge. It was continually

in bankruptcy — and everybody else was

bankrupt, too.

"But one day the wife of Lincoln L. Cleaves,

who was the account executive on Flit at the

McCann-Erikson advertising agency, failed to get an

appointment at her favorite hairdresser and went to a

second-rate hairdresser's, where they had second-rate

magazines around.

"She opened Judge while waiting to get her hair

dressed, and she found this picture. She ripped it out

of the magazine, put it in her reticule, took it home,

bearded her husband with it, and said, 'Lincoln,

you've got to hire this young man; it's the best Flit ad

I've ever seen.'

"He said, 'Go away' He said, 'You're my wife,

and you're to have nothing to do with my business'

"So, she pestered him for about two weeks, and

finally he said, 'All right, I'll have him in, and I'll buy

one picture'

"He had me in. I drew one picture — which I

captioned 'Quick, Henry, the Flit!' — and it was published.

"Then, they hired me to do two more — and

seventeen years later I was still doing them.

"The only good thing Adolph Hider did in

starting World War II was that he enabled me to join

the Army and finally stop drawing 'Quick, Henry, the

Flit!'

"I'd drawn them by the millions — newspaper

ads, magazine ads, booklets, window displays,

twenty-four-sheet posters, even 'Quick, Henry, the

Flit!' animated cartoons. Flit was pouring out of my

ears and beginning to itch me."

The Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, the

manufacturers of Flit, had another product with

which Geisel was to become concerned, in an ad

campaign that led to something of a naval career for

"Dr. Seuss".—

"They had a product called ‘Esso Marine' a lubricating

oil for boats, and they didn't have a lot of

money to spend on advertising.

"They decided to see what we could do with

public relations. So, Harry Bruno, a great PR man,

Ted Cook and Verne Carrier of Esso, and I cooked up

the Seuss Navy.

"Starting small at one of the New York motorboat

shows, we printed up a few diplomas, and we

took about fifteen prominent people into membership —

Vincent Astor and sailors like that, who had

tremendous yachts — so we could photograph them

at the boat show receiving their certificates.

"We waited to see what happened. Well, Astor

and Guy Lombardo and a few other celebrities hung

these things in their yachts. And very soon everyone

who had a putt-putt wanted to join the Seuss Navy.

"The next year we started giving annual banquets

at the Biltmore. It was cheaper to give a party

for a few thousand people, furnishing all the booze,

than it was to advertise in full-page ads.

"And it was successful because we never mentioned

die product at all Reporters would cover the

"At the time war was declared, in 1941, we had

the biggest navy in the world. We commissioned the

whole Standard Oil fleet, and we also had, for example,

the Queen Mary and most of the ships of die U.S.

lines.

"Then, an interesting thing happened. I left to

join the Army. And somebody said: 'Thank God,

Geisel's gone, he was wasting a great opportunity. He

wasn't selling the product. We have Seuss Navy hats,

and we have Seuss Navy glasses and Seuss Navy

flags.' He said, 'These things should carry advertising

on them.'

"They put advertising on them, and the Navy

promptly died. The fun had gone out of it, and the

Seuss Navy sank."

Concurrently with his advertising and promotional

activity relating to Flit and Esso Marine, "Dr.

Seuss" continued to contribute to the humor magazines;

but he was not entirely free.—

"My contract with the Standard Oil Company

was an exclusive one and forbade me from doing an

awful lot of stuff

"Flit being seasonal, its ad campaign was only

run during the summer months. I'd get my year's

work done in about three months, and I had all this

spare time and nothing to do.

"They let me work for magazines, because I'd

already established that. But it crimped future expansion

into other things."

Restless to explore new avenues of activity,

Geisel ultimately hit upon the notion of preparing a

volume for children.—

"I would like to say I went into children's-book

work because of my great understanding of children.

I went in because it wasn't excluded by my Standard

Oil contract."

Another evident cause for his focusing on the

possibility of doing books at some point was a commission

he received to provide "Dr. Seuss" illustrations

for an anthology of amusing gaffes unconsciously and

innocently perpetrated by school children, a work by

Alexander Abingdon that styled itself as "compiled

from classrooms and examination papers."—

"The book was originally published in England,

where it was called Schoolboy Howlers. Some smart

person at Viking Press in New York (I think it was

Marshall Best) brought out a reprint of the English

edition, under the title Boners.

"Whereupon hundreds of teachers in the U.S. A.

began sending in boners from their examination papers.

And the Boner Business boomed."

Boners and its sequel, More Boners, were both

published in 1931.—

"That was a big Depression year. And although

by Depression standards I was adequately paid a flat

fee for illustrating these best sellers, I was money-

worried. The two books were booming and I was not.

"This is the point when I first began to realize

that if I hoped to succeed in the book world, I’d have

to write, as well as draw."

The actual coming into being of a book of his

own, the first of what was to be so substantial and celebrated

a series of volumes written and illustrated by

"Dr. Seuss" derived from a curious stimulus and

through decidedly unusual means.—

"I was on a long, stormy crossing of the

Atlantic, and it was too rough to go out on deck.

Everybody in the ship just sat in the bar for a week,

listening to the engines turn over: da-da-ta-ta, da-da-

ta-ta, da-da-ta-ta....

"To keep from going nuts, I began reciting silly

words to the rhythm of the engines. Out of nowhere

I found myself saying, 'And that is a story that no one

can beat; and to think that I saw it on Mulberry

Street'

"When I finally got off the ship, this refrain kept

going through my head. I couldn't shake it. To therapeutize

myself I added more words in the same

rhythm.

"Six months later I found I had a book on my

hands, called And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry

Street. So, what to do with it?

"I submitted it to twenty-seven publishers. It

was turned down by all twenty-seven. The main reason

they all gave was there was nothing similar on the

market, so of course it wouldn't sell.

"After the twenty-seventh publisher had turned

it down, I was taking the book home to my apartment,

to burn it in the incinerator, and I bumped into

Mike McClintock (Marshall McClintock, Dartmouth

1926) coming down Madison Avenue.

"He said, 'What's that under your arm?'

"I said, 'That's a book that no one will publish.

I'm lugging it home to burn.'

"Then, I asked Mike, 'What are you doing?'

"He said, 'This morning I was appointed juvenile

editor of Vanguard Press, and we happen to be standing

in front of my office; would you like to come inside?'

"So, we went inside, and he looked at the book

and he took me to the president of Vanguard Press.

Twenty minutes later we were signing contracts.

"That's one of the reasons I believe in luck. If I'd

been going down the other side of Madison Avenue,

I would be in the dry-cleaning business today."

And what reception did the public accord And

to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, when the

book was released in 1937?—

"In those days children's books didn't sell very

well, and it became a bestseller at ten thousand

copies, believe it or not. (Today, at Beginner Books, if

we're bringing out a doubtful book, we print twenty

thousand copies.)

"But, we were in the Depression era, and

Mulberry Street cost a dollar — which was then a lot of

money.

"I remember what a big day it was in my life

when Mike McClintock called up and announced: I

just sold a thousand copies of your book to Marshall

Field. Congratulations! You are an author.'"

In addition to favorable sales, the comment of

one particular reviewer was especially significant in

encouraging the fledgling author of children's books

toward further effort in this new-to-him field.—

"Clifton Fadiman, I think, was partially respon-

sible for my going on in children's books. He wrote a

review for The New Yorker, a one-sentence review.

"He said, ‘They say it's for children, but better

get a copy for yourself and marvel at the good Dr.

Seuss's impossible pictures and the moral tale of the

little boy who exaggerated not wisely but too well.'

"I remember that impressed me very much: If

the great Kip Fadiman likes it, I'll have to do another."

Another he did do (The 500 Hats of Bartholomew

Cubbins, in 1938) and then another and another and

another — to the point that there have been to date

nearly fifty volumes of his authorship, in addition to

widely acclaimed motion pictures and animated

In 1955 Ted Geisel returned to Dartmouth in

order that his alma mater might, fondly and proudly,

bestow upon him an honorary degree. President John

Sloan Dickey's citation on that occasion proclaimed:

"Creator and fancier of fanciful beasts; your

affinity for flying elephants and man-eating mosquitoes

makes us rejoice you were not around to be

Director of Admissions on Mr. Noah's ark. But our

rejoicing in your career is far more positive: as author

and artist you single-handedly have stood as St.

George between a generation of exhausted parents

and the demon dragon of unexhausted children on a

rainy day. There was an inimitable wriggle in your

work long before you became a producer of motion

pictures and animated cartoons; and, as always with

the best of humor, behind the fun there has been intelligence,

kindness, and a feel for humankind. An

Academy Award-winner and holder of the Legion of

Merit for war film work, you have stood these many

Designed and printed by

The Stinehour Press.