Reencounters with Colonialism:

New Perspectives on the Americas

editors (all of Dartmouth College)

Mary C. Kelley, AMERICAN HISTORY

Agnes Lugo-Ortiz, LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES

Donald Pease, AMERICAN LITERATURE

Ivy Schweitzer, AMERICAN LITERATURE

Diana Taylor, LATIN AMERICAN AND LATINO STUDIES

Frances R. Aparicio and Susana Chávez-Silverman, eds. Tropicalizations: Transcultural Representations of Latinidad

Michelle Burnham, Captivity and Sentiment: Cultural Exchange in American Literature, 1682–1861

Colin G. Calloway, ed., After King Philip’s War: Presence and Persistence in Indian New England

Dartmouth College

PUBLISHED BY UNIVERSITY PRESS OF NEW ENGLAND

HANOVER AND LONDON

Dartmouth College

Published by University Press of New England, Hanover, NH 03755

© 1997 by the Trustees of Dartmouth College

All rights reserved

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF NEW ENGLAND publishes books under its own imprint and is the publisher for Brandeis University Press, Dartmouth College, Middlebury College Press, University of New Hampshire, Tufts University, and Wesleyan University Press.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Burnham, Michelle.

Captivity and sentiment: cultural exchange in American literature, 1682–1861 / Michelle Burnham

p. cm.—(Reencounters with colonialism—new perspectives on the Americas)

Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index.

ISBN 0–87451–818–0 (cl. : alk. paper)

DOI: 10.1349/ddlp.775

1. American literature—Colonial period, ca. 1600–1775—History and criticism. 2. American literature—Revolutionary period, 1775–1783—History and criticism. 3. American literature—19th century—History and criticism. 4. Intercultural communication in literature. 5. Sentimentalism in literature. 6. Imprisonment in literature. 7. Imperialism in literature. 8. Colonies in literature. 9. Slavery in literature. 10. Slaves in literature.

I. Title. II. Series.

PS186.B87 1997

96–49268810.9'358—dc21

4.Paul Revere, Bloody Massacre perpetrated in King-Street, Boston…, 1770

6.The horrors of war a vision Or a Scene in the Tragedy of K: Rich[ar]d: 3, December 1, 1782

7.“JOIN or DIE,” Boston Gazette, May 21, 1754

9.Benjamin Franklin, MAGNA BRITANNIA: her Colonies REDUC’D (circa 1766)

The effects of innumerable exchanges are inscribed throughout this book. I pay tribute to some of those exchanges here, if only as a way of acknowledging my continuing indebtedness. Neil Schmitz, Ken Dauber, Deidre Lynch, and Bill Warner were among the earliest and best readers of this project, and I am grateful for their advice and encouragement. Of its most recent readers, I thank particularly Don Pease and Mary Kelley for their careful and helpful responses to the manuscript, which has benefited much from their comments. Many readers responded helpfully to sections of this project at various stages in its development; I thank especially Nancy Armstrong, Dwight Atkinson, Paula Backscheider, Bob Daly, Tim Dykstal, Jim Holstun, Susan Howe, and Stacy Hubbard for their responses and suggestions. Some of the ideas in this book were presented as lectures at Auburn University, and I appreciate the exchanges and dialogue generated there among colleagues and graduate students. Taylor Stoehr helped set me on my way at the very beginning and read the manuscript with care later on; I know that I would have done well to adopt more of his excellent suggestions. And without the members of our Buffalo reading group, this book may never have come into existence; many thanks to Gail Brisson, Eric Daffron, Anna Geronimo, Julia Miller, and Juliana Spahr.

I have been fortunate in receiving a research grant-in-aid from the Office of the Vice President for Research at Auburn University, which enabled me to travel to The Newberry Library in Chicago, and a summer research grant from the College of Liberal Arts at Auburn University. I am grateful also to Dennis Rygiel for granting me the release time necessary to complete the project. Phil Pochoda at the University Press of New England has been generous in his support and enthusiasm for this project. Finally, thanks to Dick Burnham and Ulla Burnham; Nicholas Burnham and Gisela Ballard; and Christina, David, and Julia Strickler. And to Chip Hebert, who asks the best questions.

Earlier versions or portions of three chapters in this book have been published elsewhere. I thank Early American Literature (EAL) for permission to reprint sections of chapter 1 that first appeared as “The Journey Between: Liminality and Dialogism in Mary White Rowlandson’s Captivity Narrative” in EAL 28:1 (1993) 60–75. A version of chapter 6, titled “Loopholes of Retreat: Harriet Jacobs’ Slave Narrative and the Critique of Agency in Foucault,” appeared in Arizona Quarterly 49 (1993) 53–73. I thank the Arizona Board of Regents for permission to reprint portions of that essay here. Chapter 2, “Between England and America: Captivity, Sympathy, and the Sentimental Novel” also appears, in slightly different form, in Cultural Institutions of the Novel, edited by Deidre Lynch and William B. Warner (© 1996 Duke University Press. All rights reserved).

October 1996M.B.

I know not, reader, whether you will be moved to tears by this narrative; I know I could not write it without weeping.

—Cotton Mather, Decennium Luctuosum (1699)

THE IMAGE OF Cotton Mather weeping over the stories of colonial Anglo-Americans held captive by Indians and his subtle injunction that readers do the same provokes the simple question with which I began this project: why does captivity, particularly the captivity of women, so often inspire the sentimental response of tears? From the biblical image of the captive Israelites weeping on the banks of a river in Babylon to the sentimental media coverage of Americans held hostage in the Middle East, the representation of captivity has invariably, it seems, been accompanied by tears—and perhaps more by the tears of spectators than by those of the captives themselves. Moreover, those tears historically have signaled a sensation of belonging that is felt as pleasurable, quite in spite of the representation of suffering that inspires it. This book repeatedly turns to moments and texts in early American cultural and literary history in which the figures of captive women have elicited this ambivalent sentimental response. It repeatedly finds that what is at stake in the fate of these figures is nothing less than the reproduction of the nation.

Most explanations of sympathy ignore its element of pleasure and accordingly miss its profound ambivalence. The easiest way to explain sympathy, for example, has been to invoke the seemingly obvious mechanism of spectatorial identification: if we are moved by scenes of confinement and homelessness, it is because we imagine ourselves in the place of the suffering captives. This formula has been repeated from at least Edmund Burke’s 1757 claim that “sympathy must be considered as a sort of substitution, by which we are put into the place of another man, and affected in many respects as he is affected” (41), to Philip Fisher’s recent description of sympathy as “equations between the deep common feelings of the reader and the exotic but analogous situations of the characters” (118). But like tears themselves, this explanation blurs rather more than it clarifies. More specifically, by focusing on the affective relation of similarity between the captive and her audience, it obscures the complex exchanges between the captive and her alien captors. In this respect, the traditional understanding of sympathy repeats the same strategies of narratives and novels of captivity. Like the media portrayal of hostage crises, captivity literature constructs and reinforces a binary division between captive and captor that is based on cultural, national, or racial difference. Since captivity typically takes place in colonial contexts of cultural as well as military warfare, this rhetorical opposition serves to justify the political and social antagonism that both propels and results from the sentimental representation of captivity.

One aim of this book is to expose critically this strategic element of captivity literature but also to complicate it by examining a further dynamic obscured by the paradigm of sympathy outlined above by Burke and Fisher. One symptom of this hidden dynamic is the fascination, the almost subversive pleasure, with which audiences have responded to captivity scenarios. After all, a surprising number of the texts studied here—from Mary Rowlandson’s captivity narrative to Uncle Tom’s Cabin—were once popular literature, even extraordinary best-sellers. Why and how does captivity literature function as escape literature, and what might the sentimentality of these texts tell us about the terms of such escape? What is the source of the pleasure that underwrites sympathetic response?

The following chapters pursue such questions by examining texts published in North America from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries that depend on a central and sympathetic figure of a captive woman. The genres studied are not always easily distinguished from one another and indeed, their shared political and affective strategies indicate exchanges between them that are muted by efforts to contain them within coherent generic boundaries. What brings together the colonial American captivity narratives, Anglo-American sentimental novels, and African American slave narratives studied here is their mutual engagement in a project much like the one Cotton Mather invokes in the epigraph above: provoking their readers to cry for their captive heroines. One key to the cultural logic that supports this response of tears is suggested by the categories in which we place these texts, since describing them requires adjectives that articulate a complex network of political and social intersections: “colonial American,” “Anglo-American,” “African American.” It is at—or more precisely, across—such intersections that I locate the sentimentalism of these texts, for their “moving” qualities are inextricably linked to the movements in and by the texts themselves across various borders. In their narrative content as well as in their circulation as print commodities, these texts traverse those very cultural, national, and racial boundaries that they seem so indelibly to inscribe. Captivity literature, like its heroines, constantly negotiates zones of contact such as the “frontier,” the Atlantic Ocean, the master/slave division, and the color line.

These borders invoke the specific and intersecting histories of colonial relations in North America, just as the notion of “contact zone” more broadly does. I take the term from Mary Louise Pratt, who defines it as “the space of colonial encounters, the space in which peoples geographically and historically separated come into contact with each other and establish ongoing relations, usually involving conditions of coercion, radical inequality, and intractable conflict” (6). Ethnohistorical studies likewise remind us that the exchanges that take place across these early American zones of contact are framed and transected by the practice of and resistance to colonialism.1 But it is Homi Bhabha’s theory of interstitiality that points to the specifically political possibilities contained within these sites of colonial contest, for such “‘in-between’ spaces provide the terrain for elaborating strategies of selfhood—singular or communal—that initiate new signs of identity, and innovative sites of collaboration, and contestation, in the act of defining the idea of society itself” (Location 1–2). Narratives and novels of captivity demonstrate that crossing transcultural borders exposes the captive to physical hardship and psychological trauma. But they also reveal that such crossings expose the captive and her readers to the alternative cultural paradigms of her captors. In collision with other, more dominant paradigms, these emergent hybrid formations can generate forms of critical and subversive agency, both within and outside the text.

These popular texts accordingly function as escape literature because their heroines so often indulge in transgressive behavior or enact forms of resistant agency, not in spite of their captivity but precisely as a result of it. The tears that so often accompany accounts of female captivity both mark and mask that agency; sentimental discourse at once conceals the movement across such boundaries and legitimizes the transgressive female agency produced by it. When writers from Cotton Mather to Susanna Rowson to Harriet Beecher Stowe invite their readers to cry, they allow them the disavowed pleasure of indulging in unlegislated escape. But they also invite their readers into a national community that is experienced affectively precisely because its claim to integrity (whether geographical or moral) depends on remembering to forget the border transgressions and colonial violence that have secured it.2 Chapters 1 and 2 trace exchanges between, respectively, settler and native populations and imperial and colonial English people in the colonial era. Indian captivity narratives emerge during this period, circulating the subversive possibilities of cultural exchange and enlisting those possibilities in the reproduction of a national community. Narratives about women, in part because their aggressive acts generally required more careful justification and posed more danger of subversion than those of men, acquired a particular cultural appeal. This ambivalent trope of female captivity becomes refigured in later historical periods to serve—and sometimes to resist—the representational and affective imperatives of American nation-building in popular sentimental novels of the revolutionary period (chapter 3), frontier romances of the Jacksonian era (chapter 4), and abolitionist literature of the decade preceding the Civil War (chapters 5 and 6).3

The traditional formulation of sympathy as an identification with those suffering figures whom we are or could be like obscures these ambivalent sites of agency and their colonialist context by positing a model that reifies and segregates cultural, national, and racial identities. Literary histories and the categories they produce frequently do much the same thing. American studies, for example, has only recently begun to reassess and critique its exceptionalist foundations by examining the ways in which national and local categories are constructed, revised, and reinvented in a complex of transnational and cross-cultural relations.4 This project contributes to that reassessment by situating captivity literature within its intercultural context and by establishing its affectivity as a function of that context. By doing so, it also interrogates the specifically sentimental appeal of the exceptionalist myth. Like the texts examined here, exceptionalist narratives of American literature and culture have historically obscured their colonialist origins and the production of cultural difference within them.

Earlier I gestured toward an alternative model for understanding sympathetic tears as a cover for the physical and imaginative violation of borders of difference. Captivity scenarios and sentimental response are in these terms mutually constitutive, dependent on the specifically colonial confrontations that produce them. This formulation resists the onetime convention of treating captivity narratives and sentimental fiction as two separate and distinct traditions whose eventual merger signaled the decline of the former. Captivity narratives have been described as degenerating—once they became influenced by eighteenth-century English novels of sensibility—from earlier, less fictional, and more religiously oriented texts into texts aimed at “commercialism” (VanDerBeets, Held Captive xxviii), written by “the hack writer gone wild” (Pearce 16), and filled with “brutality, sadomasochistic and titillating elements, strong racist language, pleas for sympathy and commiseration,” and depictions of women as helpless “frail flowers” (Namias 37). But the tendency to locate the source of this influence in the purportedly English origins of the novel hints that, in some accounts at least, a more specifically nationalist anxiety might inflect this narrative of corruption and diminishment. After all, captivity narratives have been consistently characterized as “uniquely American” (Levernier and Cohen xxvii), as the “first distinctively American literary genre” (Lang, “Introduction” 21) and as a site in which “a particularly American discourse regarding our historical identity” (Fitzpatrick 3) was articulated.5 The more insistently the line of distinction between genres and the line of exception between continents is drawn, however, the more cloaked become the critical interstitial spaces between them.

Recent studies have moved toward understanding the more sentimentalized captivity narratives as productive of critical cultural possibilities rather than corruptive of aesthetic or national standards, and they therefore usefully revise the story of “progressive degeneration” (Ebersole 101) imposed by earlier critics on the genre. Christopher Castiglia, for example, persuasively argues that, by virtue of their very implausibility, sentimental captivity tales allowed women writers to articulate for themselves and their readers otherwise unimaginable feminist alternatives.6 Emphasizing instead the religious function of reading practices, Gary Ebersole reminds us that the sentimental portrayal of captivity inspired a somatic experience in its contemporary readers that worked to assure them of their own moral virtue (117–29). For all their differences, these two accounts have in common a privileging of the emotional relation established between the white female captive and her implicitly white (and largely female) audience, a focus that follows the definition of sympathy shared by Edmund Burke and Philip Fisher as an identification based on resemblance. But as I suggested earlier, that relation ignores the Amerindian captors who formed the backdrop and support for these sentimental equations and who frequently became the victims of that equation. These texts put into circulation critical and feminist materials, but those materials depend on the cultural surplus generated in exchange with groups that are simultaneously slated for destruction, removal, or exploitation. For these reasons, the validation of sentimentalism must be wary of repeating sentimentalism’s own concealment of the “conditions of coercion, radical inequality, and intractable conflict” (Pratt 6) that characterize colonialist borders.

In this context, Laura Wexler’s critique of Victorian America stands out for its attention to sentimental culture’s well-camouflaged practice of violence, especially on those “others” who failed to meet its standard of feeling and selfhood. As much as it legitimized those who managed to “accommodate to its image of an interior,” sentimental fiction depersonalized those who could not (17). Wexler’s analysis, developed in response to arguments by Philip Fisher and Jane Tompkins on behalf of sentimental fiction’s subversive political potential, indicates that radical claims made on behalf of that fiction have overlooked its practice of “tender violence.” This insight calls for a skepticism toward the critical tendency to sentimentalize sentimental literature, a skepticism that chapter 4, for example, develops more specifically by investigating how frontier romances and political rhetoric in the 1820s worked to reproduce the contexts of imperialism and nationalism from which they derived their affective support.7 At the same time, however, this study seeks to locate moments of critical resistance enabled by hybrid formations generated within scenarios of cultural exchange. In order to locate and identify those formations, the deconstruction Wexler performs on sentimentalism’s falsely maintained opposition between public and private must be extended beyond the domestic national borders within which her analysis remains. Just as captivity narratives have been positioned within a rhetoric of exceptionalism, American sentimental novels have been read within isolated national and cultural contexts, encouraging a persistent lack of attention to the ambivalent products of the contact zone, where cultural difference emerges amid colonial exploitation.

This paradigm extends back at least to Leslie Fiedler’s Love and Death in the American Novel, a text notable not only for its often cited castigation of sentimentalism but for its development of a theory of American literature around the materials of captivity narratives. Fiedler locates “what is peculiarly American in our books” (n.p.) in the culture-crossing adventures of frontier heroes like Daniel Boone and Natty Bumppo. What makes “the American novel … different from its European prototypes” (11) is its story of the white male’s flight from the woman-centered home into the wilderness inhabited by dark men. What finally enables the “Americanness” of American literature to be realized, according to this account, is the successful exorcism of the artistically enfeebling influence of sentimental novels. Fiedler’s fleeing frontier heroes are therefore mirrored in the flight of “American” novelists and critics away from the “sentimental travesties” (89) written by Susanna Rowson and Samuel Richardson, as Nina Baym first noted in her classic article on “how theories of American fiction exclude women authors” (“Melodramas”). The myth of exceptionalism is therefore founded on a gesture that, by aligning sentimental fiction both with women and with Europe, at once masculinizes and isolates American literature. The explosion of scholarship on women writers and sentimental fiction that accompanied and followed Baym’s critique has continued to interrogate and challenge that gendered division.8 But this important body of scholarship has given less challenge to the nationalist division and its segregationist effect. In fact, the isolationist foundations of American literary history have been as often reinforced as they have been dismantled by the inclusion of this once marginalized body of literature. As a result, the transnational and intercultural origins of sentimental discourse and the very reliance of sentimentality on the kinds of colonial relations associated with contact zones have continued unacknowledged.

In her influential defense of sentimental fiction, for example, Jane Tompkins makes a case for its conformity to existing theories of American literature, arguing that critics have falsely described these novels as “turning away from the world into self-absorption and idle reverie” (143). Thus, a novel like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, she contends, focuses on the home merely as “the prerequisite of world conquest” (143); no less than contemporary domestic advice manuals, Stowe’s novel harbors an “imperialistic drive” to “coloniz[e] the world in the name of the ‘family state’ under the leadership of Christian women” (144). This redescription might qualify sentimental fiction and the women who wrote it for inclusion within various theories of American literature from which they have been silently exiled, including Sacvan Bercovitch’s study of the uniquely American jeremiad or definitions that insist on the expansionist imagination within American books.9 At the same time, Tompkins’s description accurately, if uncritically, points to the ways in which sentimental fiction can participate in a project of cultural and religious imperialism that has not only domestic but global pretensions.10 However “American” a novel like Uncle Tom’s Cabin may be, for example, to isolate it within national borders is to miss its colonizing transcontinental reach into Liberia and the implications of that reach for abolitionism and racial ideology within the United States (implications examined in chapter 5). The moving bodies of captive women documented in the books studied here are inscribed by tensions between, on the one hand, their service to national or cultural reproduction and, on the other, the threats they pose to such reproduction. It is precisely this irresolvable tension between national agents and minority agency that sentimental discourse adjudicates. As chapter 3 maintains in its discussion of republican motherhood, agency’s ambivalent oscillation between autonomy and dependence is implicit in the very origins of U.S. political formations and their sentimental constructions of national belonging.

In his own act of exorcising sentimentalism, Leslie Fiedler makes a confession that betrays a different sort of difficulty posed by writers of sentimental novels like Susanna Rowson, one that has nothing to do with his own overt concerns with standards of aesthetics or masculinity. These writers, he explains, “sometimes moved back and forth between the old country and the new with an ease which distresses the classifier” (67). Captivity and Sentiment is concerned with the interstitial sites marked precisely by these two paired indicators: the distress of classifiers and the mobility of bodies. While critics have sometimes placed captivity literature and sentimental literature in contest with each other on a field defined and critiqued in terms of gender, that field has been consistently surrounded, as it were, by an isolationist fence that has blurred the relations of contestation that take place on and across its containing borders. As chapter 2 argues, bringing eighteenth-century stories of female captivity into transcontinental dialogue highlights the arenas of friction and exchange that exceptionalist paradigms of American studies, like sentimental nationalism, conceal. The texts studied in this book often resolutely inscribe the boundaries on which isolationism and exceptionalism depend, but attending to their transgression of those same borders encourages them also to circulate as the unwitting bearers of cultural difference within American literary and national histories.

Captivity and Sentiment locates agency at those overlooked sites of cultural difference. The category of agency has been an ongoing source of concern within cultural studies, in large part as a result of the dilemma posed by the model of agency and its containment associated with the work of Foucault. That model posits a relationship between subject and structure that operates on the trope of captivity, as Foucault’s interest in institutions of confinement like the prison, the clinic, and the asylum might suggest. The prospect of subjects incapable of escaping from or altering the political and cultural structures in which they are confined has generated, as if in sympathy for those subjects, a substantial and wide-ranging body of critical response. Chapter 6 turns to this conceptual border, the dividing line between subject and structure, in order to demonstrate that debates about agency have faltered by leaving this boundary intact. It is the hybrid and unpredictable effects of cultural exchange documented in Harriet Jacobs’s slave narrative that brings into relief this fissure and its political possibilities, overlooked equally by the Foucauldian analysis of agency and its Lacanian critique. Practicing the colonial strategies of resistance that Homi Bhabha positions within the eclipsed regions of interstitiality, Jacobs’s narrative exposes the limitations to the sentimental sense of national belonging so often mobilized by the tradition of captivity literature within which it is written. The example of Harriet Jacobs in the final chapter illustrates that critical agency is generated in sites of exchange and also that such agency purchases a measure of its efficacy by exploiting the very structures of confinement from which it enables bodies to escape. The resistant and unrecuperable surplus of cultural difference always left over by the process of cultural exchange finally speaks to the crucial necessity of identifying what sentimentality hides as well as what it allows.

The conclusion turns to two examples, Briton Hammon’s obscure eighteenth-century slave narrative and the popular 1991 science fiction film Terminator 2, which illustrate what can get lost behind the blinding veil cast by tears. It argues for sustaining an interculturalism that would engage sites of exchange between and within texts, alongside and within multiculturalism’s sometimes sentimental emphasis on traditions defined and distinguished by coherent cultural, racial, or national categories. The intercultural spaces that sometimes go unremarked between those categories tell a history of colonialism in North America, a history in which both crosscultural captivity and sentimental discourse have their origins. In turn, these ambivalent colonial arenas call for a more critical assessment of the role of sentimentalism in U.S. nationalism. They also call for an increased attention to the ways in which those representations a spectator most identifies with, is most moved by, have been, in Gayatri Spivak’s words, “secured by other places” (269).

MARY WHITE ROWLANDSON’S 1682 captivity narrative begins with her careful recollection of the violent scene of Indian attack on her Lancaster, Massachusetts, home, where she watches her own imminent fate rehearsed as nearby houses burn and their inhabitants are killed or taken captive. “At length,” she writes, “they came and beset our own house, and quickly it was the dolefullest day that ever mine eyes saw” (118).1 For two hours, she estimates, the Indians “shot against the House, so that the Bullets seemed to fly like hail; and quickly they wounded one man among us, then another, and then a third” (118–19). She watches her sister and her nephew die, while a bullet passes through her own side and wounds the daughter she carries in her arms. When the Rowlandson house is set on fire, she is forced to take her children and depart, with “the fire increasing, and coming along behind us, roaring, and the Indians gaping before us with their Guns, Spears, and Hatchets to devour us” (119). Mary Rowlandson’s abandonment of her “roaring” home and her entrance into the hands of the “gaping” Indians retrospectively marks her transition into a physical and cultural homelessness that would resist psychological and ideological closure long after her experience of Indian captivity came to an end.

Within a short time after this raid but in what seems an immeasurable cultural distance, Rowlandson would be sewing shirts for and declining tobacco from the Wampanoag sachem Metacom, whom the English called King Philip. King Philip’s War erupted in June 1675 and was followed by a series of surprise raids like this February 10 one by Narragansett Indians on the frontier settlement of Lancaster. A number of southern New England tribes had joined with Metacom’s Wampanoags to resist the effects of growing Euro-American hegemony in the region, including diminished land, contests over political power, and property disputes.2 But because the Indians typically took English captives away with them after skirmishes such as the Lancaster one, the conflict between these two cultures was often represented in terms of another kind of property: human property. Captives served as tools of economic negotiation and as figures of political and religious significance as they circulated between the New England tribes and the New England colonists. The body of the captive, exchanged as an unusual sort of commodity between two social and military antagonists, consequently told a history in which often contradictory economic, cultural, and religious signs were articulated.

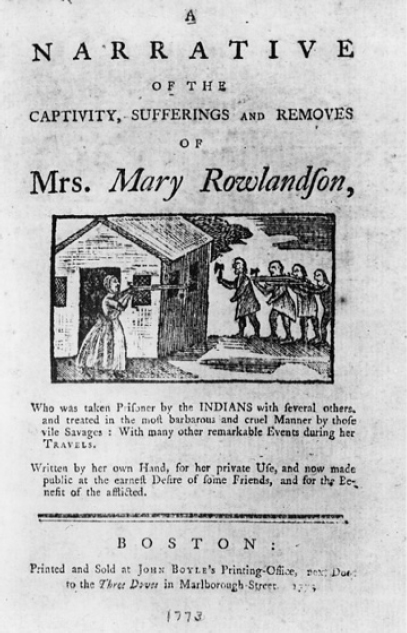

Rowlandson’s narrative ends with a tone of calm and a noticeable absence of descriptive detail, in striking contrast to its opening representation of the violent attack on Lancaster. Two woodcuts in a 1771 edition of Rowlandson’s narrative nicely illustrate this stylistic shift from her narrative’s first frantic scene to its rather orderly and routine conclusion. The first portrays the fearful chaos of the Lancaster raid, as figures raise their arms in grief and flight from a collection of burning houses (fig. 1). Asecond woodcut that appears near the end of the narrative portrays the captive calmly discussing the terms of her ransom with the Indians Tom and Peter (fig. 2).3 Rowlandson barely records her return to the Puritan community and does not mention at all her reunion with her husband and children. Instead, she closes the narrative with a list of providences that retroactively expose God’s plan to test severely but ultimately deliver the Puritan project in New England.

This interpretive framework is consistent with that supplied in the preface to her book, which is signed “Ter Amicam” and has been attributed to Increase Mather. Mather’s preface reinforces the theological significance of Rowlandson’s experience by presenting her story as a singular example “of the wonderfully awfull, wise, holy, powerfull, and gracious providence of God,” which should “be exhibited to, and Viewed, and pondered by all, that disdain to consider the operation of his hands” (114).4 If Rowlandson experienced conversion through captivity, Mather implies, then her readers should experience conversion as a result of reading about her captivity: “Reader, if thou gettest no good by such a Declaration as this, the fault must needs be thine own. Read therefore, Peruse, Ponder, and from hence lay by something from the experience of another against thine own turn comes, that so thou also through patience and consolation of the Scripture mayest have hope” (117). In Mather’s view, the vivid details offered in scenes like the opening description of Indian attack would, if read properly, inspire this edifying result.

FIG 1. Woodcut of the raid on Lancaster, from A Narrative of the Captivity Sufferings and Removes of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson (Boston, 1771). Photo courtesy of Edward E. Ayer Collection, The Newberry Library.

FIG 2. Woodcut of the captive Mary Rowlandson with the Indians Tom and Peter, from A Narrative of the Captivity Sufferings and Removes of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson (Boston, 1771). Photo courtesy of Edward E. Ayer Collection, The Newberry Library.

It is difficult to know, however, whether readers responded as Mather insisted they should. His preface was eliminated from later editions of the narrative, and Rowlandson’s initial self-proclaimed statement of purpose emphasizes not the conversion to spiritual propriety but the relation of a personal history: “and that I may the better declare what happened to me during that grievous Captivity,” she writes, “I shall particularly speak of the severall Removes we had up and down the Wilderness” (121). Rowlandson’s narrative retroactively attempts to collate and comprehend the meaning of her unprecedented cultural circulation as a commodified captive. She lived and traveled with her Algonquin captors in the New England wilderness for nearly three months, and the narrative she wrote upon her return records her extraordinary experience of cultural contact. For the most part, that contact was characterized by perpetual conflict, for the captive was daily forced to confront the incommensurability between the English culture she left behind and the Algonquin one she was forced to inhabit. This Puritan Englishwoman’s extended habitation within the radically alien culture of her Indian captors necessarily makes her narrative a history of transculturation and of a subjectivity under revision.

Such conflict and its effect on the texture of Rowlandson’s account has become, for recent readers, the most fascinating aspect of her text, and the instant popularity of her narrative suggests that seventeenth-century readers also responded to those elements in her story that set it apart from much of the literature available in Puritan New England.5 Indeed, the circulation of her text is no less important than Rowlandson’s own circulation. Her book was one of the most popular in seventeenth-century New England and was read widely in both the old and the new worlds. Charles H. Lincoln suggests that “[n]o contemporary New England publication commanded more attention in Great Britain or in America” (110) than her narrative, and Frank Luther Mott lists the book as the first prose best-seller in America (20). The first edition of her narrative was reputedly exchanged between so many hands that no copy of it survives.

This link between Rowlandson’s experience and her culture’s fascination with it is perhaps best expressed in the irony that what may have been the first example of escape literature in America was a narrative about captivity. Even as the Puritans and the Algonquins negotiate the possession of this captive-commodity, Rowlandson’s text, in its effort to “the better declare what happened to me,” documents her own attempt to negotiate between Puritan and Algonquin cultural practices. This entangled exchange produces tensions and contradictions in her narrative, such as the difference between the urgently narrated opening scene of fire, bloodshed, and death and the composed complacency of those concluding passages acknowledging the work of providence. Such contradictions in turn carve out transgressive spaces that resist definition by or accommodation within either Algonquin or English cultural paradigms, spaces that therefore unwittingly escape dominant Puritan ideology and theology. The dangers and possibilities of cultural exchange within the colonial contact zone would generate literary and political strategies associated with the secular genre of the novel, within whose sentimental discourse scenarios of captivity and escape would continue to be explored and exploited.

The Mirror of Typology

Mary White Rowlandson was the wife of Lancaster’s Puritan minister, the daughter of the town’s wealthiest original landowner, and the mother of three surviving children. Other than these familial relations, almost nothing is known of Rowlandson’s life before her captivity. When she peered from her Lancaster home onto the scene of “gaping” and “devouring” Indians, what did this New England woman know about those men and women who were to become her captors? Given the language barrier and the Puritan aversion to the Papists, it is unlikely that she was familiar with the representations of Indians in earlier captivity narratives written by French Jesuits and Spanish conquistadors. English people were forbidden to live with the Indians (Vaughan 208–9), but Indians were sometimes employed as servants or apprentices in New England homes or businesses, and there is evidence to suggest that the Rowlandson household contained at one point such an Indian servant.6 These indentured Indians were usually Christianized, and they constituted a group for whom Rowlandson clearly had little affection or respect, for in her narrative she singles out betrayals of the English by various “Praying-Indians” (152) and particularly remarks on the “savageness and bruitishness [sic] of this barbarous Enemy, I [aye], even those that seem to profess more than others among them” (122).7

When Puritan New Englanders like Rowlandson happened to employ or meet individual Indians, they were likely to be such Christianized Indians who, at least since the Pequot War several decades earlier, had been increasingly compelled to abandon their traditional economies (Salisbury, Manitou 238). Furthermore, the religious typology that structured Puritan hermeneutics encouraged the colonists—especially during periods of warfare—to perceive the Indians as agents of Satan, designed to tempt and test the election of individual Puritans and the integrity of the New England project as a whole.8 It is clearly by way of such typology that Mary Rowlandson orders and understands her own experience with her captors. In the introductory section of her narrative, for example, before it becomes structured into a series of “removes” that recount Rowlandson’s stages of travel through the wilderness, she compares the destruction she has witnessed to the misfortunes of Job, whose possessions were destroyed by agents of Satan as a test of faith. Of the thirty-seven inhabitants of her household, Rowlandson notes, twelve were killed, twenty-four taken captive, and “one, who might say as he, Job 1.15, And I only am escaped alone to tell the News” (120). In similar fashion, Mather in his preface likens her trial “to those of Joseph, David and Daniel” (114).

Rowlandson refers to the Indians in these first few pages as “murtherous wretches,” “bloody Heathen,” “merciless Heathen,” “Infidels,” “a company of hell-hounds,” “ravenous Beasts,” and “Barbarous Creatures” (118–21). During the first night of her captivity, she observes “the roaring, and singing and danceing, and yelling of those black creatures in the night, which made the place a lively resemblance of hell” (121). Such descriptions are consistent with typologically informed perceptions of the Indians such as those offered in contemporary accounts of King Philip’s War,9 and the Puritan Rowlandson repeatedly casts her experience in terms of both specific and general biblical precedents. In this context, Rowlandson’s captivity represents a version of the Babylonian or Egyptian captivity of the Israelites at the same time that, as David Downing notes, she “presents her captivity as an image of the unredeemed soul in the hands of the devil” (256).

Typology ideally operates through a structure of equivalence, in which events in scripture reflect and foretell the outcome of events in the world, just as figures and incidents in the Old Testament prefigure those in the New Testament. This process, which Erich Auerbach refers to as figural interpretation, requires the substitution of a biblical event or person with an earthly event or person, “in such a way that the first signifies not only itself but also the second, while the second involves or fulfills the first” (73).10 Typology’s central mechanism, therefore, is something like a mirror, allowing one set of events to be substituted for another provided the two bear some reciprocal resemblance. Once made, that substitution facilitates the prediction of secular history by providing a model within which to interpret the significance of historical outcomes. If Mary Rowlandson’s trial mirrors that of the captive Israelites, then her own good piety coupled with God’s providence should lead her to redemption. As Auerbach explains, “an occurrence on earth signifies not only itself but at the same time another, which it predicts or confirms, without prejudice to the power of its concrete reality here and now. The connection between occurrences is not regarded as primarily a chronological or causal development but as a oneness with the divine plan, of which all occurrences are parts and reflections” (555). History becomes mediated through and is made comprehensible by its analogy to scripture, just as the figures of William Bradford and John Winthrop in Cotton Mather’s Magnalia Christi Americana are representative types that allegorize New England’s history even as they repeat the histories of Moses and Nehemiah. Once the initial typological substitution is made, the Puritan struggle in the New World comes to seem no less inevitable than its eventual success.

Early criticism of Rowlandson’s narrative tended to highlight her use of typology and, as a result, to place her text within an orthodox Puritan literary and theological tradition.11 More recently, however, this narrative has gained interest and status as a text that unwittingly breaks with and even subverts that tradition. This subversion, however, does not result from Rowlandson’s misuse or abandonment of typology. It occurs rather because her use of typology begins to fracture, to fall in upon itself. Increasingly, toward the end of her narrative, where her recourse to scriptural quotations and analogies multiplies, typological relations become unable to contain the accumulation of details and events she has recorded. The assumed equivalence between her categorical knowledge grounded in Puritan English culture and her daily experience gained among the Indians begins to collapse. The simple substitution of experience for knowledge and of the Algonquin cultural practices she encounters for her Puritan assumptions and beliefs about the Indians becomes suspended in a moment of negotiation that resists the closure that typology would impose on it. And because substitution fails, succession fails; the anticipated outcomes predicted by typological relations are not only delayed, but they risk nonarrival. The integrity of Puritan epistemology and the teleology of history stall at this moment of undecidability, when the mirror of typology begins to reflect distortions.

Those distortions result from Rowlandson’s liminality, from her partial and stunted transculturation to Algonquin tribal life; they mark the subjectivity effects of her experience of cultural exchange. The influence of her unprecedented cultural mobility on her text and on the Puritan English society in which that text circulated has been underestimated in critical discussions of this narrative, which for the most part have assigned contradictions in the narrative to Rowlandson’s psychological trauma rather than to her cultural circulation. At least since Richard Slotkin’s early analysis of the discrepancies in Rowlandson’s narrative technique, critical attention has focused on what is often referred to as the two “voices” in this text,12 a narrative dichotomy whose most striking effects occur in the moments when Rowlandson’s description of her participatory experiences contradict the interpretive conclusions she draws from them, when her record of an Indian’s sympathy and generosity nevertheless leads her paradoxically to declare the universality of Indian savagery and barbarity. These are precisely those moments of inequivalence, those moments of typology’s reflective failure.

Because there is absolutely no acknowledgment of such failures in the text itself, it is difficult to determine whether its author and its earliest readers were fully aware of these contradictions. There is nothing in either Rowlandson’s prose or Increase Mather’s preface to indicate an awareness of the dissonance between her portrayal of the Indians as savage and cruel and her descriptions of individual Indians who are kind and sympathetic. How then are we to explain the emergence of this representation of the Indians as humans, as a culture rather than as a type, within a text that cannot articulate such a possibility? How do these figures escape their containment, their own captivity, within Puritan ideology? Mitchell Breitwieser locates this “realism” in a conflict between the individual psychology of its author and the demands of her Puritan culture, arguing that Rowlandson’s unsuccessful attempts to repress her grief enable “a human Indian figure [to] come into view at the margin of perception” (132).13 Yet the absence of “human” Indians from other captivity narratives, an enormous number of which were told or written by grieving mothers whose infants died during captivity, suggests that such trauma cannot fully account for the realism of Rowlandson’s text. It is necessary to consider as well the significant effects of transculturation, the inevitable exchanges of language, material goods, modes of behavior, and ideological orientations that characterize the scene of Indian captivity. In this context, Mary Rowlandson’s captivity narrative stands out not because of her experience of grief but because it records so many of these kinds of transactions. The recollective language of her text reveals the effects of cultural liminality, of a functional adaptation, however partial, to Algonquin tribal life. Rowlandson’s psychic disorientations, therefore, indicate the anxiety of adjustment to an alien culture as much as they signify a response of grief at the loss of a familiar one, and it may in fact be this transculturation as much as her mourning that Rowlandson feels she must repress. In other words, when typological equivalence fails or falters, it signals the activity of other forms of exchange.

The Friction of Exchange

Rowlandson acknowledges her commodity status as a captive, her simultaneous use value and exchange value for her captors, when she observes that her mistress, Weetamoo, a Pocasset Indian married to the Narragansett sachem Quinnapin, refused to lend her to another Indian for fear of losing “not only my service, but the redemption-pay also” (151). The practice of captive-taking predates European contact, when, as Colin Calloway notes, captives were usually either adopted or tortured to death as a way of replacing or avenging the death of a family member lost in war. That practice persisted but was also revised within the new colonial economy that emerged between natives and settlers, when a developing market value for European captives prompted Indians to begin selling them for ransom (“Uncertain Destiny” 195). Although hardly a commodity in the sense that a gun or a piece of gold is, in this hybrid colonial economy the captive nevertheless circulated as an object of trade subject to some of the same cross-cultural translations and investments that inscribed other commodities. In periods of warfare, captives became one of many common objects of exchange between Europeans and Indians, who, despite the lack of a shared language or culture, had always participated extensively in trade with each other. Specific accounts of exchanges between them illustrate, however, that certain values could not and need not be so easily agreed upon. When they were acquired by the Indians, for example, items such as gold pieces were perforated and strung onto wampum necklaces, and gun barrels were sawn off so that they could be played as flutes or whistles. Copper kettles were sometimes cut up into arrowheads or game pieces (Axtell, European 256), and sometimes placed on the heads of the dead, while stockings were used as tobacco pouches (Sturtevant 86–87). When Henry Hudson gave the Delaware Indians iron hoes, they wore them about their necks until sailors who arrived the next year taught them how to make handles (Axtell, European 256).14 As Alden Vaughan suggests, the Europeans’ desire for land and their practice of placing beaver pelts on their heads may have struck the Indians as equally absurd (329). Though it did not produce the practice of taking captives, colonialism did produce the market for captives, just as it produced the market for these other goods. And by situating the Indian captive within this arena of exchange between cultures, the fluctuating movements and values prompted by that exchange come vividly into relief.

Rowlandson notes that although her master is the Narragansett sagamore Quinnapin, she was “sold to him by another Narrhaganset Indian, who took me when first I came out of the Garison” (125) in Lancaster. Although she does not mention the terms of that first sale, her record of it indicates a relatively common phenomenon of Indian captivity in colonial America: captives often underwent a series of exchanges and owners, sometimes traded within the tribe and sometimes between tribes. Her son Joseph, for example, after tarrying too long during one visit with his mother, angers his master who “beat him, and then sold him. Then he came running to tell me he had a new Master” (144). This serial process of successive exchanges established through relations of equivalence is overshadowed in Rowlandson’s narrative by the protracted negotiations leading up to her eventual ransom, when as a commodity she is substituted for another whose value she mirrors.15 Her narrative in fact stands as a record of the precarious status of the captive-commodity within the suspended period and the hybrid space that precedes her removal from the borderland of cultural exchange.

If Rowlandson’s narrative brings our attention to this moment, it also requires that we extend the concept of exchange to include not merely economic transactions but also cultural and linguistic transactions. The traditional as well as the coerced mobility of the Algonquins necessarily brought them into frequent contact with foreign groups, encouraging not only the exchange of products but the assessment of values that are not merely economic. The work of anthropologists in general and of ethnohistorians of colonial North America in particular attest to the existence and significance of such exchanges.16 The trade of goods is only one aim or result of cultural contact; education or religious conversion were often equally predominant goals, and changes in language, attitude, or behavior were as frequently their effects. James Axtell calls this process “cultural warfare” (Invasion Within 4), and indeed these other forms of exchange—social, ideological, linguistic—reveal the conflict that underlies any seemingly placid process of exchange, for such transactions are frequently unsolicited, accidental, even violent and are seldom entered into with the pleasure one might associate with the marketplace of commodity exchange. As a result, these transactions indicate the friction at the center of any act of exchange.

This friction characterizes the suspended moment of substitution; it marks the struggle between cultures, languages, or commodity owners for power, predominance, or profit. In the process the friction can produce emergent forms, new linguistic or behavioral modes that come to occupy a space between the cultures or languages that frame them. The friction of cultural conflict opens up spaces that escape and frequently transgress those structures whose contact produces them. My analysis of Rowlandson’s text focuses on precisely this site of conflict and exchange, where the process of substitution has commenced but is not yet complete, where the stasis of negotiation forestalls the movement of succession. This liminal site, this hinge that both separates and joins two collaborators who are at the same time opponents, is the site of the captive. Within such a space and at such moments in the process of exchange, the captive is effectively between owners, between cultures, between identifiable values. As long as negotiation continues, the relation of equivalence that determines economic value—and cultural values—remains unestablished.

Once negotiation ceases and the course of a transaction is complete, each commodity becomes something else, for the process of substitution and succession necessarily produces continual transformation, the change within exchange. As commodities change hands, the commodity itself changes, becomes inscribed by the friction of exchange. When the commodity exchanged is a human subject, such inscription can not only alter the subject itself but can disturb or confuse the discourse and culture that finally incorporate it. If subjectivity, like value, is formed through relations of equivalence with others,17 then circulation within a foreign system of value(s) necessarily reassesses and revises that subjectivity, just as value is reassessed and revised when commodities are put into circulation. Once value has been determined and substitution has taken place, the friction of exchange appears absorbed within the seeming stability of commodity ownership or of cultural coherence but not without having created a potential out of which new types, new subjectivities, and new positions for resistance and power can emerge. Thus, with the eventual exchange of Mary Rowlandson for twenty pounds, her suspended cultural identity and liminal subjectivity appear resolved; she is purchased by her husband and reclaimed by Puritan New England. The seeming simplicity of such a transaction belies, however, the residual inscription of her body, her text, and her subjectivity by the experience of Indian captivity.

In other words, cultural exchange produces a supplement, an extraordinary kind of surplus. The cultural or ideological surplus resulting from the circulation of the captive is profoundly ambivalent; it constitutes not a differential that leads to addition but an “additional” that signifies difference. The production of this cultural supplement is the production of cultural difference, in the sense Homi Bhabha gives it: cultural difference “addresses the jarring of meanings and values generated in-between the variety and diversity associated with cultural plenitude”; cultural difference inhabits “that intermittent time, and interstitial space, that emerges as a structure of undecidability at the frontiers of cultural hybridity” (“DissemiNation” 312; emphases added). Thus, the surplus left over after the event of cultural exchange is like the “‘difference’ of cultural knowledge that ‘adds to’ but does not ‘add up’” and therefore “is the enemy of the implicit generalization of knowledge or the implicit homogenization of experience” (313). This supplement inhabits that contested space marked out by the act of exchange, a space often characterized by an extreme anxiety. Such anxiety, evident in Rowlandson’s text as well as in Increase Mather’s preface to it, highlights by concealing the fact that this surplus can threaten to disrupt the apparent homogeneity and stability of the system that absorbs it. I am interested here, then, in what the stories of captives tell us about the economics of cultural exchange and about what might be called the cultural anthropology of captivity as a kind of economic exchange.18 It is precisely such cross-cultural exchanges that can produce a surplus able to contest and destabilize the presumed autonomy and homogeneity of monocultural systems.19

Liminality and Transculturation

Indian captivity, as it was documented in colonial America, was an occasion for the simultaneous invention and destruction of the self. The captive occupies a liminal position, suspended in the cleavage that divides one cultural paradigm from another, and this tenuous and anxious status necessarily inflects the discourse of the recently redeemed captive. The anthropologist Victor Turner positions liminality as the second of three stages in rites of initiation, as the margin or threshold between separation from a community and reaggregation into it (196).20 Unlike Turner’s model, however, Rowlandson’s experience of liminality is not a process that takes place within a single culture but one that places her between two separate and distinct cultures, a site produced by colonialism. Far from reproducing the recognizable patterns of social ritual, her dramatic and traumatic event of liminality oscillates between two systems of belief and ritual in a constant condition of the unexpected. By faithfully recording the resultant interactions and conversations between herself and the Indians, Rowlandson’s captivity narrative reveals the challenge these exchanges and dialogues posed to Puritan ideology. This text’s narrative dichotomy and its ideological contradictions are grounded in the linguistic and cultural exchanges that make up so much of the detail of Rowlandson’s story.

The captive’s journey separates her from English culture, the Puritan community, and the domestic family. The division of her narrative into “removes” enhances the sense that with each successive departure the captive becomes increasingly distant from her own culture and moves further and further into a wilderness familiar only to her Algonquin captors. That separation necessarily produces changes in the captive’s behavior, attitudes, and subjective sense of self, changes evident in her detailed record of the gradual process of transculturation she undergoes over the twelve weeks of her captivity. Resistant as she is at first to Indian food, she grows accustomed to it, and while it was at first “very hard to get down their filthy trash,” by the third week that which “formerly my stomach would turn against” became “sweet and savoury to my taste” (131). Although she remains all but deaf to her captors’ humor, she does become increasingly sensitized to the intricacies of Indian cultural expression. Early in her captivity Rowlandson hears an account of a female captive who, along with her child, complained of homesickness so frequently that the Indians finally “made a fire and put them both into it” (129), a story she relates with unqualified horror and fear. Much later in her narrative, when the Indians tell her that they have roasted and eaten her son, she skeptically dismisses the tale after “consider[ing] their horrible addictedness to lying, and that there is not one of them that makes the least conscience of speaking the truth” (141).

Her skill in sewing and knitting allows Rowlandson to begin to assume a distinct role within the Indian community.21 Not only does her production of clothing, stockings, and hats increase her interaction with the Indians, but it gives her a significant position within their economy. She is paid for her work, and she reintroduces that payment back into the tribe, either by trading for other goods, sharing her edible earnings, or simply offering her payment—“glad that I had anything that they would accept of” (136)—to her master. Several times, Mary Rowlandson refers to the Indian camp as “home” (136), and she notes that one particularly dreary campsite was blessed with nothing but “our poor Indian cheer” (129). Her inconsistent use of pronouns likewise reveals an often confused cultural identification. During the seventh remove, for example, she begins by associating herself with the Indians: “After a restless and hungry night there we had a wearisome time of it the next day.” However, as the group arrives at “a place where English cattle had been,” at “an English path” and “deserted English fields,” it is the objectified Indians who take “what they could” from the forsaken land (although Rowlandson admits that “myself got two ears of Indian corn”). At the end of this scene she suddenly identifies herself instead with the English, claiming that the stolen corn would serve as “food for our merciless enemies [the Indians],” though she goes on to conclude that “that night we had a mess of wheat for our supper” (132–33, emphases added), including herself again among the Indians.

In two of the later removes, Rowlandson betrays the extent of her immersion in Indian society. During the seventeenth remove, after a day of travel, she remembers that “we came to an Indian Town, and the Indians sate down by a Wigwam discoursing, but I was almost spent, and could scarce speak” (148). Such a claim suggests that the captive would on other occasions “discourse” with the Indians, but was too “spent” to participate this time. Similarly, during the nineteenth remove, when the captive is called to a counsel, she notes that she “sate down among them, as I was wont to do, as their manner is” (151), again suggesting a comfortable understanding of at least the basic tribal customs and language. Though the Indian language is transcribed only once (148), Rowlandson repeatedly refers, both directly and indirectly, to conversations between herself and the Indians. These conversations reveal a development in Rowlandson’s ability to converse with her captors, as well as a growing complexity of interaction that involves both a greater mutual interest and a greater shared hostility.

Rowlandson’s first recorded dialogue with her captors is characterized by the mutual suspicion that marks their earliest exchanges, for in response to the Indians’ request that she “[c]ome go along with us,” Rowlandson extracts a promise that if she complies she will not be hurt (120). Later that first night the Indians deny her request to sleep in an abandoned English house, insisting that she share their conditions rather than continue to “love English men still” (121). By the third remove, however, an Indian makes a remarkable concession to her own cultural requirements by offering her a Bible and promising that she will be permitted to read it, while in the seventh remove another Indian is visibly intrigued by her willingness to eat horse liver, which, Rowlandson recalls, “I told him, I would try, if he would give a piece, which he did” (132–33). These two exchanges alone signify a fascinating process of growing cross-cultural recognition, if not one of culture blending, that was hardly operative at the outset of her captivity. Meanwhile, her relationship with her master, Quinnapin, develops to the point where he “seemed to me the best friend that I had of an Indian,” while that with her mistress, Weetamoo, degenerates to such a level that Rowlandson’s complaints and requests are met with slaps, denials, and an “insolency [which] grew worse and worse” (139). By the thirteenth remove, the captive’s emergent ability to negotiate the cultural and linguistic divide between herself and her captors allows her to serve as a mediator and perhaps as a translator between the new English captive, Thomas Read, and the Indians, who were “all gathered about … asking him many Questions.” When Read, “crying bitterly,” tells Rowlandson his fears that he will be killed, she “asked one of them, whether they intended to kill him; he answered me, they would not” (142). This remarkable exchange suggests that Rowlandson had a capacity to communicate with the Indians that Read, for one, lacked.

The narrative’s language of recall and its record of linguistic exchanges reveal that Rowlandson’s immersion in Amerindian culture places her in a culturally liminal subject position that is no longer commensurable with, though by no means alien to, the Puritan and English subjectivity with which she entered captivity. However, as transculturated as Mary Rowlandson becomes and as much regard as she grows to assume for her Indian master, she hardly becomes Indianized and certainly does not find a replacement for her domestic ties among the Indians. While many Anglo-American captives were adopted and underwent a process of cultural integration by ultimately joining the tribes that took them captive, Rowlandson remains in a resistant liminal state, that “no-man’s land betwixt and between” (Turner 41) one cultural paradigm and another. Later captives, like Eunice Williams and Mary Jemison, married Indian men, spent the remainder of their lives as members of the Indian tribal community, and repeatedly refused pleas to return to white settlements. Their illiteracy and, in Williams’s case, loss of facility with the English language leave their experiences a difficult matter of historical reconstruction.22 Amid that silence, Rowlandson’s narrative offers one account of such exchange and the friction that characterizes it.

Mary Rowlandson recorded her experience as a captive in the postliminal period following her return to Puritan society, and her narration of past events is inflected both by a residual cultural liminality and by the dominant Puritan culture from which she was removed and to which she returned. In retrospect, her captivity seems to her a type of spiritual pilgrimage during which her sanctity and election were tested, “in which the Lord had His time to scourge and chasten me” (167). Yet it was not only the individual Puritan Mary Rowlandson who was tested during this journey; her discourse was tested as well. By the time she wrote her narrative, the daily challenge that Amerindian culture posed to that discourse had receded, and her Puritan worldview—like her family—had been largely restored. Yet the challenge to New England Puritan discourse, as remote as it may have seemed to Mary Rowlandson once she was ransomed and to the English once they have won King Philip’s War, is nevertheless recorded in the intercultural dialogue inscribed in her best-selling narrative. The very urge to write of her experience in order to “the better declare what happened to me” attests to her memory’s resistance to easy containment within available Puritan modes of understanding, perhaps in part because her experience of transculturation led her to encounter examples of female political and economic autonomy that transgressed the roles for women defined by her own society.

Transgression and the Anxiety of Motherhood

Mary Rowlandson’s captivity narrative entered public circulation only with some degree of anxiety. Despite his explicit conviction that this text contains an important and exemplary lesson in piety, Increase Mather’s preface is littered with apologetic justifications for its publication. Not surprisingly, these anxious apologies collect around the issue of gender. Mather seems to want to protect this female author from aspersion and to deliver her from rumor. “I hope by this time,” he writes, “none will cast any reflection upon this Gentlewoman, on the score of this publication of her affliction and deliverance” (115). He claims that “this Gentlewomans [sic] modesty would not thrust it [her narrative] into the Press” except at the insistence of “[s]ome friends” (115), and he therefore insists that “[n]o serious spirit, then (especially knowing any thing of this Gentlewoman’s piety) can imagine but that the vows of God are upon her. Excuse her then if she come thus into publick, to pay these vows” (116). It is as if, by describing circulation in the spiritual terms suggested by the act of “paying vows,” Mather hopes to detract attention from the circulation of both Rowlandson and her narrative.

Mather’s apologies signal a common seventeenth-century anxiety in New England about the conjunction of publicity and women, an anxiety exemplified by Anne Bradstreet’s brother when he responded to the publication of her poetry by claiming that “[y]our printing of a Book, beyond the custom of your sex, doth rankly smell” (Parker 63; qtd. in Koehler 31) and by the Puritan authorities in their earlier condemnation and exile of Anne Hutchinson. The public mobility of women led to suspicions of, if not accusations against, their virtue. Such rumors also characterized the response to Mary Rowlandson’s captivity and redemption, for one of the several narratives of King Philip’s War published in London in 1676 claims that

There was a Report that they had forced Mrs Rowlinson to marry the oneeyed Sachem, but it was soon contradicted; For being a very pious Woman, and of great Faith, the Lord wonderfully supported her under this affliction, so that she appeared and behaved her self amongst them with so much courage and majestick gravity, that none durst offer any violence to her, but on the contrary (in their rude manner) seemed to shew her great respect. (New and Further 5)

Clearly there was some speculation—on both sides of the Atlantic and long before the publication of her narrative—about this captive’s virtue. Such speculations are hardly surprising considering that circulation by women has as often been perceived as a threat to society as the exchange of women has been called the fundamental basis of it. What is surprising is that no public record, to my knowledge, announces such speculations about Rowlandson without dismissing them in the same sentence. This example might be taken to illustrate a remarkable rule: transgression by female captives repeatedly escapes the kind of censure that accompanies so many other kinds of female transgression; transgression within captivity is always, sometimes quite amazingly, legitimated. One critic argues that Rowlandson escapes censure because she appears to accept the patriarchal arrangement of Puritan society and to adopt the commensurate role of Puritan goodwife (Davis 50). This assessment fails to note, however, that Rowlandson’s narrative teeters on the very edge of telling an entirely different story about women, quite in spite of its explicit acceptance of the Puritan social order.

Mary Rowlandson’s was the first captivity narrative written in English, and it was also the first book originally published in New England that was written by a woman.23 Her narrative is unique not only for its account of cultural exchange but because it delivers an early and rare female voice to the textual documents of Puritan America. It is therefore necessary to be attentive to the gendered accents that inflect the cultural dialogue between Puritan and Indian inscribed in her text. Her narrative not only records a specifically Puritan Englishwoman’s view of her Algonquin captors but documents her assumption of a role among them that is a radical alternative to available roles for colonial New England women. If the cultural surplus contained in this text registers an incipient critique of Puritan ideology, it also harbors a potential feminist critique of Puritan society. Again, this surplus is largely concealed, since the narrative does not overtly stage these critiques so much as it unwittingly performs them by putting the material for such critical positions into circulation. In this case, that material resides in the contrast between Rowlandson’s goodwife status in patriarchal Puritan society and her status as independent producer-exchanger within the Indian community, revealed in the careful depiction of her daily life among the Algonquins. If the effects of Rowlandson’s cultural circulation sometimes escape their containment by scripture, typology, and conventional seventeenth-century literary forms, the effects of her circulation as a Puritan woman threaten to escape her insistent and anxious self-definition as a mother and as a dependent Puritan wife.24

The experience of captivity involves a constant oscillation, not only between Puritan and Indian subjectivities but between a whole series of selfdoublings. One of the most fascinating of these is Mary Rowlandson’s simultaneous occupation of the noncirculating position of the mother and the exchangeable one of the captive. Following Levi-Strauss, Luce Irigaray argues that Western patriarchal society “is based upon the exchange of women” (This Sex 170), who circulate as commodities between men. Irigaray goes on to divide these “women-as-commodities” into the categories of private use value and social exchange value, represented by the figure of the mother and the virgin. The mother’s status is analogous to private property, unavailable for exchange; whereas the virgin who awaits exchange on the marriage market represents, like the captive, pure exchange value. Rowlandson’s status as both mother and captive introduces to this model a complicating revision that locates resistance within the confining patriarchal order outlined by Irigaray.

From the very beginning of her narrative, Mary Rowlandson defines herself as a mother. She writes that at the approach of the attacking Indians “I took my Children … to go forth and leave the house,” but her escape is cut off by a barrage of bullets, one of which penetrates “the bowels and hand of my dear Child in my arms” (119). The ensuing captivity effectively begins for Rowlandson with a violence directed against her motherhood, for she claims that “[t]he Indians laid hold of us, pulling me one way, and the Children another” (120). The early part of her narrative focuses on Rowlandson’s concern for her wounded daughter Sarah, whom she continues to carry in her arms. After Sarah’s death, Rowlandson’s concern immediately shifts to her other two children, who are held captive among different but nearby groups of Indians. She struggles to maintain contact with them, and even when that contact becomes impossible, she continues to worry over their physical and spiritual welfare. Captivity thus removes Rowlandson’s children from her sight and subjects them to the surveillance of the Indians. Her dead daughter Sarah is taken and buried without her knowledge, while her other children are subjected to the discipline of distant and alien others. Rowlandson laments the absence of her children, claiming that “I had one Child dead, another in the Wilderness, I knew not where, the third they would not let me come near to”; but she also expresses anxiety that she “should have Children, and a Nation which I knew not ruled over them” (126). Her motherhood has been usurped and her maternal supervision over her children incapacitated.

Yet Rowlandson’s maternity is not erased so much as it is held in suspension. As she represents it, her maternal gestures appear to her captors as ineffectual and senseless as her orthodox Puritanism. In response to her wounded daughter’s incessant moaning, her captors warn her that “your Master will knock your Child in the head” (125); and when she goes to visit her daughter Mary after Sarah’s death, “they would not let me come near her, but bade me be gone” (126). Because the Indians appear not to understand, or at least do not respond properly to, Rowlandson’s maternal or religious gestures, those gestures inevitably fail to produce their intended effects. In the terms of the model proposed by Irigaray, Rowlandson’s use value is effectively suspended along with her motherhood. From the perspective of the Puritan society from which she has been abducted, her maternal use value becomes eclipsed by a reinstated exchange value, for as soon as she is taken captive, Rowlandson is quite literally put back on the market. Because the captive must be purchased by her Puritan husband from her new Indian master, she becomes once again a commodity for exchange between males. Thus, Mary Rowlandson undergoes, as a captive, a symbolic revirginalization in the sense that she once more becomes an object of exchange, and this shift is evident in her home culture’s patent concern over her virtue.25

Indeed, Rowlandson’s narrative betrays its own concern with the threat to the exchange value of female captives, even or especially to captives who are mothers. At one point Rowlandson relates a story about a pregnant woman whom the Indians reputedly “stript… naked, and set… in the midst of them; and when they had sung and danced about her … they knockt her on head” (129). Perhaps in response to such tales as well as in defense of rumors about her own virtue, Mary Rowlandson more than once insists that “not one of [the Indians] ever offered me the least abuse of unchastity to me, in word or action” (161). Clearly, Rowlandson is defending less her captors than herself from the accusations of seduction, or even rape, that she expects from her own society. Such defenses of her chastity might also be seen as a means through which Rowlandson maintains her exchange value. Her captors force her to estimate that value when they call her into an Indian council and ask her to declare “how much my husband would give to redeem me” (151). Her own price quote is then duly delivered to Boston, as part of the negotiations between her Indian owners and her Puritan husband over the sale and repurchase of the recommodified Mary Rowlandson.